posted by Dave Arnold

Low-Temperature and Sous-Vide Primer Contents:

- Purdy Pictures: Sous-Vide and Low-Temp Charts

- **I . Introduction to Low-Temperature Cooking and Sous-Vide** you are here

- II. Low-Temperature Cooking Without a Vacuum

- III. Use and Abuse of the Vacuum Machine andVacuum Tricks

- IV. Temperature Control and Safety

- V. Cooking Meats and Poultry

- VI. Cooking Fish

- VII. Cooking Everything Else

Part I. Introduction to Low-Temperature Cooking and Sous-Vide

- 1. Getting the Terms Right

- Low-Temperature Cooking Defined

- Sous-Vide Defined

- 2. Some Uses and Advantages of Low Temperature Cooking

- Uniform Cooking, Increased Consistency, and Shifting Control to the Chef

- Shifting Work from Service to Prep (or from Party to Prep at Home)

- Low-Temp for Insurance

- Low-Temp for New and Novel Textures

- Low-Temp for Increased Tenderness

- 3. Low Temperature Cooking Disadvantages

- Surface Browning, the Maillard Reaction, and the Challenges of Low-Temperature Cooking

- Uniformity of Texture

- 4. Why do Chefs Use Sous Vide?

- Sous-Vide for Economy

- Storage

- Organization

- Sous-Vide for Effect

- Texture Modification

- Flash Pickling and Vacuum Marination

- Forming

- De-airing

- Sous-Vide for Economy

1. Getting the Terms Right:

Sous-vide and low-temperature cooking are just two of the many techniques and processes that are revolutionizing modern cooking. Despite their growing popularity, many remain confused about the difference between low-temperature cooking and sous-vide—including equipment manufacturers. Between the two, low-temperature cooking is undoubtedly the more important.

Low-Temperature Cooking Defined:

Cooking low temperature does not mean cooking food to a lower internal temperature than is traditional. Low-temperature cooking refers to the temperature of the cooking medium, not the final temperature of the food being cooked. A rare steak has the same internal temperature whether cooked low-temperature or traditionally. Low temperature cooking is defined as any cooking procedure where the cooking temperature is at or close to the desired final internal temperature. There are two basic requirements for low-temperature cooking:

- precise and accurate temperature control;

- a cooking medium which conducts heat more efficiently and accurately than dry air. Water and water vapor are typical, but oil, stock, or any other liquid will work.

By way of example: to cook a steak to an internal temperature of 55°C (131°F), you could either sear it and put it in a 205°C (400°F) finishing oven till it reaches 55°C (131°F) (not low temperature cooking), or quickly sear it and throw it into an oil bath maintained at 55°C (131°F) (low temperature cooking but not sous-vide).

In traditional high-temperature cooking, the temperature of the cooking medium is almost never the same as the desired temperature of the food. That is, while your oven may be heated to 205°C (400°F), your fry oil can to 190°C (375°F), and poaching water to 100°C (212°F), a steak cooked in those mediums can only be considered rare when it reaches an internal temperature of 54°C (129°F). The difference between the desired final food temperature and the temperature of the cooking medium is referred to as temperature delta, or ΔT (pronounced “delta t,” the triangle is the Greek letter delta). You should just get used to referring to ΔT’s –like, “hey, you want that squab cooked to 56°C? Do you want to use a ΔT?”

Sous-Vide Defined:

In contrast, the simplest way to define sous-vide may be to refer to its French meaning, “under vacuum.” Anything associated with a vacuum machine is sous-vide. In restaurants, the sous-vide process usually (but not always) consists of:

- placing products into impervious plastic bags

- putting those bags under vacuum

- heat sealing those bags

- releasing the vacuum

- further manipulating, processing, or storing

This is where it gets confusing: sous-vide techniques are often used for low temperature cooking, but not all sous-vide cooking is low-temperature cooking. The classic example of this is boil-in-bag meals. The cooking medium is boiling water—not low temperature. Yet, because there is a vacuum process involved, it is sous-vide. That said, sous-vide is very effective for low-temp cooking because food inside the bags neither dries out nor loses flavor during prolonged cooking if proper temperature is maintained. The vacuum bags also eliminate evaporation and evaporative cooling. The temperature of the food’s surface becomes identical to the cooking temperature after a short time.

Chefs and diners alike often confuse sous-vide and low-temperature cooking. Sous-vide must involve a vacuum process; but the food may be cooked at high or low temperatures. About 90% of what cooks want to achieve with low temperature cooking can be achieved without a vacuum.

2. Some Uses and Advantages of Low Temperature Cooking:

Uniform Cooking, Increased Consistency, and Shifting Control to the Chef:

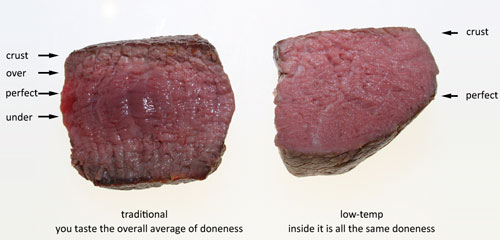

Traditional cooking typically uses a high ΔT. Foods cooked in this manner display an overcooked portion on the exterior. Meat cooked at high temperatures does not have one level of doneness—it is tasted as an average, from the well-done exterior to the less cooked center. Low-temperature cooking is less forgiving, because there is no way to average out errors. In a steak cooked at a low ΔT, the steak retains the same temperature throughout. The difference of 2°C can make a large difference in texture when there is no averaging effect—you need good temperature control (The entire range of steak doneness, from rare to well-done, is only a matter of 14°C (25°F). Luckily, modern equipment easily gives us temperature control accurate down to a tenth of a degree, which means we can cook products extremely uniformly and get them right 100% of the time.

Uniformity can be a disadvantage—no one wants a giant piece of roast beef that is one color all the way across—but most of the time uniformity is an advantage because it leads to increases consistency. Your steaks will never be over or under –always just right. This advantage cannot be overstated, and it applies to restaurants or home cooks. Additionally, because the hard work of reaching the correct internal temperature is being regulated by an accurate piece of equipment, the responsibility for getting the product right is shifted away from the line cook towards the chef who is choosing the temperature and setting the machine.

Shifting Work from Service to Prep (or from Party to Prep at Home):

We can always make more prep time. Service is what service is. Any time we can shift work away from service towards prep we win. Many low temp techniques require more prep time than their traditional counterparts; but are blindingly fast to finish off at service time. The high speed finish derives from the fact that the food is pre-cooked and can be held warm and ready to go, only needing a few seconds of finishing time. Speed finishing is a boon to the home cook as well. Parties are a lot more fun when you can hang out with your guests and all your food is in perfect finish at the same time.

Low-Temp for Insurance:

Low-temp cooking can provide a type of cooking insurance by guaranteeing a minimum doneness. Here’s how:

- 1. Low temp your food to the rarest you want it. The food is now uniformly rare.

2. Cool the product completely.

3. Cook the product traditionally, but focus only on obtaining the perfect exterior because the middle is already cooked. You have insured that the inside is done.

Here are some examples of low-temp for insurance:

- Roasts can be challenging. Often you get a good crust before the middle is done and then overcook the whole piece to bring up the center. Other times, you focus on getting the middle perfect but end up with a poor crust. Low-temp insurance fixes that. Low temp the roast till it is rare and cool it down. Put the roast in a high oven and pull it when the crust is perfect—you have already insured that the middle is done.

- On a beef Wellington it is very difficult to insure that the puff pastry and the beef come out nicely at the same time. Usually the meat is overcooked or the pastry is too blond. With low-temp insurance you sear and pre-cook and cool your tenderloin and then wrap it in puff pastry. Now, you can turn your oven up and just focus on getting the pastry nice and brown since your meat is already cooked.

- Sausages are often poached before being finished in a pan on the grill. This is high-temp cooking insurance. Instead, low temp-cook the sausages (60-62°C is usually good), then finish them on a grill or in the pan. The low-temp pre-cook doesn’t overcook the meat and rely on fat alone to provide juiciness.

- Duck breast is best cooked with low-temp insurance. Pre-cook the breast to 57°C and cool it down. Then just focus on crispy skin.

Low-temp for insurance tends to produce items that have textures and appearances very close to traditionally cooked items, just better and more consistent. Because the products have a traditional feel, many cooks like this technique.

Low-Temp for New and Novel Textures:

Low-temperature cooking also allows for the production of some textures that were traditionally unattainable. Three examples:

- Super-low temp fish: Fish heated at extremely low temperatures, around 50°C or (122°F) to an internal temperature of 42°C (107°F), has a dense, fudge-like or custard quality unattainable with high ΔT cooking. This type of cooking is controversial; many chefs dislike the texture attained with these methods, and some scientists believe the techniques are unsafe. Other chefs believe that the traditional cooking method overcooks fish and that the low-temperature method is best.

- Low temperature braises: In a typical braise, meat with a lot of connective tissue is cooked at a high temperature for several hours. The high temperature and several hours is what is needed to break down the collagen into gelatin. This process overcooks the muscle and dries it out. Luckily, the gelatin re-moistens the overcooked meat and produces a delicious braise. When a meat is under-braised, it seems tough and dry because the collagen hasn’t melted into juicy, water holding gelatin. With low temperature cooking, however, we can hold a tough piece of meat at a very precise temperature for a very long time. If a short rib is held at 6o°C (140°F) it will maintain a lightly pink, medium-cooked color for days. The texture of the muscle fiber itself will also remain somewhat static. The connective tissue, on the other hand, won’t break down over the course of 3 or 4 hours at this temperature—you need to cook it for two full days. At the end of these two days, however, you will have a completely pink, completely tender short rib that is a dream to slice and portion.

- Creamy egg yolks: When you heat a whole in-shell egg in water to 63°C (145°F), the yolk becomes creamy—not runny, not set. One degree lower is a runny yolk. One degree higher is a set yolk. The 63°C egg is a delight and completely impossible to make traditionally. More on eggs later.

Low-Temp for Increased Tenderness:

Low-temperature cooking can also produce meats that are more tender than normal. Enzymes responsible for some of the benefits of dry-aging meat increase activity as the temperature rises. These enzymes are most active right before they denature, between 49°C and 54.4°C (120°F and 129.9°F). Because low-temperature cooking allows meat to stay in this zone longer than traditional cooking, meat is more tender than normal. Traditionally, a large piece of meat heated for a long period of time, such as a roast, remains tender. Low-temperature cooking makes it possible for smaller pieces of meat to be held at these low temperatures for longer periods of time.

3. Low Temperature Cooking Disadvantages

Surface Browning, the Maillard Reaction, and the Challenges of Low-Temperature Cooking:

Low-temperature cooking does not produce crisp, flavorful, brown exteriors, which are usually obtained by cooking at high temperatures. Much of the artistry of low-temp cooking involves getting around this limitation. Some techniques include:

- Using meaty, savory flavors like soy sauce and miso (both are high in umami).

- Quick-searing meats for flavor either before they are cooked, right before they are served, or both. Quick-searing in low-temperature cooking is performed at a higher than normal temperature to develop a brown crust without overcooking the interior of the meat.

- Browning bones, fat, inexpensive pieces of meat, or vegetables and putting them into the vacuum bag along with the main food before cooking. The savory notes of the added pieces permeate the food over time. Roasted fat is especially useful, as many of the characteristic flavors of different meats are generated by the taste of cooked and broken down fats.

Uniformity of Texture:

The biggest gripe people have with low-temp cooking is that the uniformity of texture. Some people say that all low temp food is “mushy.” While it is true that bad-low temp food is mushy, good low-temp food doesn’t have to be. One of the ways to guard against uniformity is to provide texture in the finishing step—usually by searing. Adding crunchy garnishes or cooking portions of the food separately to compensate for the lack of textural variety is another option. A chicken breast cooked sous-vide, for example, might be served with a piece of crispy fried chicken skin (although we have had good chicken this way, we find the skin served this way not as satisfying as good-old crispy skin that is still stuck to the chicken). Lastly, European chefs often cook with a moderate ΔT (usually 10-15 C) to “overcook” the outside of the food and provide some textural variation. Most Americans don’t cook this way because it require precise temperature measurement, precise timing, or both. Most Americans cook with 0 ΔT and add texture in the finishing step.

4. Why do Chefs Use Sous-Vide? Sous-Vide for Economy and Sous-Vide for Effect

Chefs may use sous-vide techniques and processes for a variety of reasons which roughly break down into two categories: sous-vide for economy and sous-vide for effect. The two approaches are not mutually exclusive, therefore it’s important to thoroughly understand both.

Sous-Vide For Economy:

Storage:

Traditionally, vacuum-packing has been used to enhance the storage life of cooked products. The bacteria that cause food spoilage need oxygen to survive. Since vacuum packaging removes all air (and therefore oxygen) from food, spoilage is slowed drastically if the proper steps are taken. Oxidation is also greatly reduced by utilizing vacuum-packing. Foods like cut apples and artichokes do not turn brown quickly in vacuum pouches. In long-term storage, vacuum bags can prevent the oxygen-produced rancidity of unsaturated fats. Low-moisture products like dehydrated fruit chips tend to stay crispy indefinitely in the low-moisture vacuum environment.

Unfortunately, some bacteria that cause illness (pathogens) are not inhibited by a lack of oxygen. In fact, some of the most dangerous bacteria thrive only in the absence of oxygen. If sous-vide products are kept in unsafe conditions, these pathogens can grow to dangerous levels without the simultaneous spoilage that would normally signal their presence. This is why it is important to adhere to safety rules when using sous-vide.

Organization:

Vacuum-packed pre-portioned foods are neat, sanitary, and easy to organize. Many portions of the same product can be fabricated at the same time and then sealed, which minimizes cross-contamination. The food is handled minimally before being placed in a sterile environment. Retrieving food is easy, and each portion is individually protected from spills and other dangers, such as a raw product dripping onto a cooked product.

Sous-Vide for Effect:

Recently, the unique properties of the sous-vide process have inspired a cooking movement that aims solely to increase the quality of food and achieve special culinary effects. Think of this as sous-vide for effect.

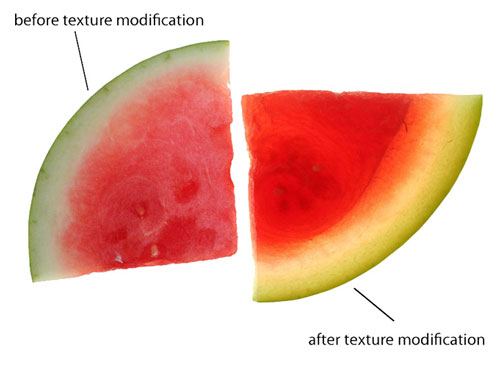

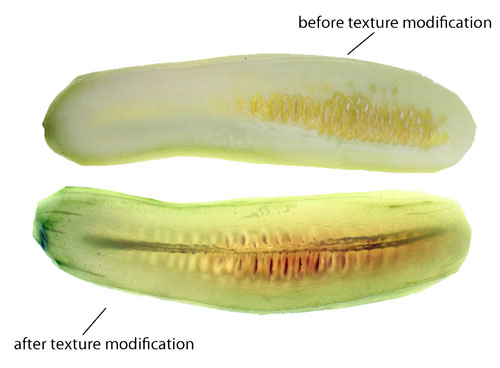

Texture Modification (aka Compression):

The key to this technique is long vacuuming to get all the air out of the inside of the food. After the food is sealed and the vacuum released, there is an immediate observable change in the product as the voids that used to contain air are compressed. On some products, the effects of compression are accentuated over time (pears become more translucent after several hours). This process can be accelerated by re-vacuuming the sealed bag until the bag inflates with water vapor and then releasing the vacuum.

Porous foods can have their texture and appearance radically modified by vacuum-packaging. Watermelon, for instance, becomes denser, changing from a mealy to a candy-like texture. Pears, cucumbers, and tomatoes become translucent.

Flash Pickling and Vacuum Marination:

Vacuum-packaging foods increases the uptake of flavorful liquids, brines, and colors. The more porous the item, the more dramatic the end results are. For example, a pear can be colored with port in an hour under vacuum. Cucumbers and other vegetables can be flash pickled in seconds. Meats can be brined in much less time than at atmospheric pressure.

Forming :

The pressure exerted by the atmosphere can be used to form dishes. Layers of food can be pressed extremely flat. Once removed from the bag, these compressed layers become easy to slice into beautiful portions. Food can be arranged as in a terrine, vacuumed, solidified, and sliced for decorative effects. Some effects formerly achieved with a simple mold and a weight can be achieved more easily with a vacuum machine.

De-airing :

When thick sauces and purées are blended, they often have large amounts of air whipped into them. Sometimes this air is undesirable. When chefs use modern thickeners and gelling agents, like xanthan gum, trapped air becomes a problem, as it affects the body of the sauce and its appearance (liquids with many air bubbles appear white and opaque). The thicker the sauce, the more difficult it is to remove air. Sauces that contain too much air can be made crystal clear by removing the air bubbles in a vacuum machine.

Any liquid can have all their bubbles removed in a vacuum machine. Place the liquid in an appropriately wide container (not a bag) inside the vacuum machine. If there is too much liquid in the container, the mixture will boil over and create a mess during the process. Close the chamber and introduce a vacuum; the liquid will start to rise and bubble. Soon after, the initial bubbles will break and the liquid will enter a rolling boil. At this point the vacuum can be released and the liquid will have cleared. This procedure is one scenario where there is no need to pre-chill the product being vacuumed because the desired outcome is to have the product boil.