posted by Dave Arnold

Nils and I wrote an article on freezing for the September 2009 issue of Food Arts magazine. The piece included a short section on liquid nitrogen (LN or LN2), and I have greatly expanded it here for the blog. Important: we make no claims to inventing any of the techniques presented here. They are all pretty standard. Please, discuss who-came-up-with-what-first somewhere else. This is simply a primer.

Sections:

I. Introduction

II. Safety (very important stuff)

III. Getting and Storing LN

IV. Some Applications (cool stuff, most of the pictures)

I. Introduction:

Liquid nitrogen is about as cold as you can get in the kitchen, registering a whopping negative 196 degrees Celsius (-321° F) … and it’s non-diluting and non-contaminating to boot. Despite its preposterous coldness, liquid nitrogen has only 15% more cooling power than the same amount of ice at 0° Celsius. This counterintuitive fact leads many chefs to underestimate the amount of liquid nitrogen they need for a given task, like making ice cream.

Ice cream is typically the first thing people make with LN. Theoretically, it should be the best you can make because the mix freezes so quickly—and the quicker the freeze, the smaller the ice crystals, and the smoother the ice cream. But commercial ice cream machines make sufficiently small ice crystals for most palates, and it’s very easy to over-freeze portions of liquid nitrogen ice cream. So your LN ice cream results might not be as great as you expect.

But there are many other fantastic LN applications. You can turn fresh herbs into powder, separate citrus fruits and raspberries into jewel-like pieces, and freeze alcohol to make liquid centered treats. Be warned: liquid nitrogen is addictive and mesmerizing in the kitchen.

II. Safety:

Nitrogen makes up most of air we breathe. It is completely and utterly non-toxic—end of story. Yes, it is a chemical. Cows and carrots are just collections of chemicals.

The dangers of liquid nitrogen, of which you must be ever vigilant, are cold-burns, asphyxiation, and pressure-related explosions.

Dangers to Your Customers:

Don’t serve items to your customers too cold. You will burn their tongue, spoil their meal, and make them angry. I am speaking from first hand experience here (as the burnee, not the burner).

Dangers to You, Your Co-Workers, and Your Building:

Cold Burns:

Some do’s and don’ts. Do wear goggles or a face shield. Do Not wear clothes that could trap liquid nitrogen—like canvas shoes. Do Not use unprotected hands to hold on to things—like this bain—that might get instantly super-chilled. I got badly burned shooting this picture and couldn’t feel my fingertips for two days.

If a small amount of liquid nitrogen touches your skin and rolls off, you will not be harmed. Lab technicians routinely dip their bare hands directly into liquid nitrogen (quickly! they don’t hold their hands in it). A layer of vapor instantly forms and temporarily protects your skin—this phenomenon is called the Leidenfrost Effect. Read a cool paper on the Leidenfrost Effect, written by a science teacher who dips his hand in molten lead here.

Burn danger occurs when liquid nitrogen remains in contact with your skin—whereupon liquid nitrogen burns the same way hot oil does. Painfully.

• Do Not wear clothing that can capture liquid nitrogen run-offs or spills, such as cuffed pants. I got my worst LN burn when my protective sleeve (which was not rated for cryogenic work—wrong choice) got too cold, cracked, and allowed LN to seep into the cloth cuff of my gloves.

• Do Not dispense LN into a container, such as a bain marie, that you are holding with your bare hands. You will get burned if the container gets super-chilled, which is likely. This hurts, too.

• Always wear safety goggles—LN can boil up and into your face at any moment, quickly blinding you. Forever.

• Never pour LN above your head, and do not kneel next to someone pouring LN.

• Do Not hold containers of LN with one hand, or in any other precarious way.

• Have a clear exit path in case something goes wrong—if you drop a whole container of LN, you and everyone else around you needs to get away from it quickly.

Explosion:

Never seal liquid nitrogen in a closed container. The pressure will rise, and unless the container can hold 1000 psi or better (nothing you have can) it will explode. In July 2009 a young cook in Germany lost both his hands and landed in a coma when he sealed LN in a closed container. Liquid nitrogen containers, called dewars, are either completely vented to the atmosphere or held between 10 and 22 psi with multiple safety valves. It’s worth repeating: don’t put LN in a container that is sealed or could become sealed by mistake.

• Let’s put that last part another way: Make sure there is no way your containers could become sealed. Example: a venting tube in a lid could get clogged, or crimped. A thermos lid you leave unscrewed can be sealed by your colleague. Note that even if an explosion isn’t strong enough to cause damage, LN spraying all over the place is hazardous.

• Never send LN through a pipe that could become sealed. You’ll make a pipe bomb.

• Never modify a dewar. In 2006 at Texas A&M, someone intentionally defeated the safety valves on a LN storage dewar. The resulting explosion destroyed several rooms, tore a hole in the ceiling, and ruptured plumbing that in turn flooded the entire building. Thankfully all this happened at 3am, and no one was hurt. The pdf report complete with pictures is: here.

Asphyxiation:

Disposable Oxygen Meter. Runs for 2 years with no maintenance—then you get a new one. 180 bucks. McMaster Carr part number: 18995T51.

A small amount of liquid nitrogen turns into a large amount of nitrogen gas—LN expands by 700 times when it vaporizes. If you use a lot of LN in a closed space, it will displace the oxygen and suffocate you before you know what’s happening. This is the largest cause of death from LN. The danger is very, very real.

Unless you have been trained like an air force pilot—by coming up to the very brink of nitrogen-induced death under highly controlled circumstances—you can’t tell that you are suffocating on nitrogen. The panicky feeling you get from choking or staying under the water too long doesn’t come from lack of oxygen— it comes from the buildup of CO2 in your blood. Your lungs can get rid of CO2 just fine in a pure nitrogen environment, so your body doesn’t send those helpful distress signals. Also, breathing pure nitrogen is much worse than just holding your breath. Breathing nitrogen actually sucks the existing oxygen out of your bloodstream. Majorly bad news. So,

• Do Not use LN in an unventilated area. What constitutes an unventilated area? Read ASU’s guidelines here.

• Never go into an elevator with LN. If a dewar breaks in the elevator, you’re dead.

• Never carry LN in a vehicle’s passenger compartment. You get into an accident, the LN spills and vaporizes, you suffocate instantly.

• If you see someone passed out near an LN tank, do not try to help. Many people who die from nitrogen suffocation were trying to help co-workers. If the victim has passed out they are probably already dead. Call 911.

• Invest in an oxygen meter, like the one shown in the picture above.

• We can’t cover every eventuality here—be sensible.

Set up and enforce a safety program:

Make sure everyone who uses LN is properly trained. Print out and post basic LN safety rules. Some documents:

An overview of the hazards (plus gruesome details) from the US Chemical Safety Board.

The cryogenic fluids handling guide from Arizona State University.

III. Getting and Storing LN:

Unlike compressed gasses, liquid nitrogen isn’t stored under high pressure. In a cylinder of nitrogen gas, the pressure can easily top 1000 psi. It can sit around at room temperature practically forever without any loss. LN, on the other hand, is always freezing cold and is kept in an insulated container (called a dewar) under little, if any, pressure. Because LN is constantly boiling off, you’re always losing a little bit. The bigger and better insulated your dewar, the longer you can store your LN. Because LN is always boiling off and venting through those all-important relief valves, your dewar will occasionally makes little psssssssssssssssss sounds. Don’t be alarmed by the hissing noise—it’s your friend.

When you are filling a container or dewar remember this: you will use up a lot of LN just chilling down the vessel. Doesn’t matter if you are filling a dewar, a bain, or a Styrofoam cooler—when you first add LN, it will smoke furiously while the surface of the container gets chilled down to LN temperatures. After the container is chilled, it will fill up in an orderly and efficient way. Rule of thumb for LN efficiency: don’t let your containers run dry and warm up if you don’t have to. Keep them cold.

The easiest way to get LN is to snag some from a buddy who has a bunch already. Use a vented vacuum insulated coffee dispenser, never a thermos! A thermos can seal and explode. Many vacuum insulated coffee pots are inherently vented. Check to make sure yours is.

We use these pots quite a bit around the school. They are convenient, easy to pour from, and they only lose about 50 percent of their volume in 24 hours. I’ve heard people tell of getting these pots filled at their local gas supplier, but I have had no such luck.

Most chefs obtain liquid nitrogen from compressed gas/welding suppliers. You’ll have two choices: buy or rent a small 10-50 liter capacity dewar and have it filled on a regular basis (few places in New York still rent these dewars), or buy or rent a large 160-240 liter capacity storage dewar and have the company swap your empties for fulls when necessary. The large dewars are much more economical; up-front costs are higher ($2000 versus $1000) but they’re much cheaper to own. You’ll pay the same amount to swap out a 160 liter dewar as you will to fill a 50 liter dewar. If a small dewar develops a leak or breaks, it’s your problem—not an issue with large dewars because they are swapped out. You can usually rent the large dewars for a small monthly fee, plus the rather large refundable deposit. One annoyance with the large dewars: you will need to prove to the supplier that you own it. They won’t swap out your dewar if they think it’s a rental from a competitor or stolen off the street from the local utility company.

Small Dewars, 10-50 Liters:

10 liter dewars are small and convenient, but they don’t have nearly the holding time of larger dewars. Remember—the larger the dewar, the smaller the percentage of LN that evaporates per day. If you have to pay someone to come with a truck and fill your dewar, 10 liter dewars are uneconomical—go for 35-50 liters.

10 liter dewar with a plain plug top. These dewars are great for moving LN from place to place and for saving the last of your LN when you send out your bigger dewar for refilling. We love Converse, but they are unacceptable in this circumstance (see the safety section).

A 10-20 liter dewar really shines if you need to carry LN from place to place, or store the last of the LN from your big dewar while it’s out being refilled. Hint: you’ll want to order LN before you run completely dry, but you don’t want to throw away the last of your LN. Save the dregs with a 10- or 20-liter plug top dewar.

Liquid Withdrawal Device:

Dewars with liquid withdrawal devices will cost you more, but they’re worth it for their convenience. Here’s an image from dewar manufacturer Taylor Wharton:

Dewar with a liquid withdrawal device. 1) Cryogenic phase separator (really, they call it that, more on that later). 2) Liquid valve. 3) Gas vent valve. 4) Pressure gauge and safety relief valves. 5) Clamping band.

The liquid withdrawal device just clamps onto an ordinary plug-top dewar. The clamp seals the top and allows the dewar to develop about 11 psi. Above that pressure, excess nitrogen is vented from a relief valve— which you will hear hissing. Sometimes, if the dewar is overfilled, the valve will get frozen open and you will lose all your LN. Try tapping the valve to shut it or gently heating it to unfreeze it. If the relief valve clogs and fails (as opposed to freezing open, which is not a safety issue, but a money issue), the secondary safety valve kicks in. Here is the operating manual for the liquid withdrawal device, including instructions on how to fill a dewar.

Big Dewars:

If you really want to be an LN ninja—and save money in the long run—buy a real dewar—160-240 liters. Here are the parts:

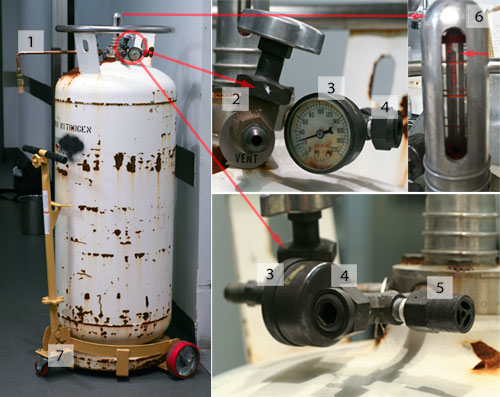

LS 160 160 liter LN dewar. 1) Liquid takeoff. 2) Gas vent. 3) Pressure gauge (should read about 20-22 psi). 4) Secondary safety valve. With any luck this will never go off. 5) Relief valve. You will hear this valve hissing. Sometimes, if the dewar is overfilled, this valve will get frozen open and you will quickly lose all your LN. Try tapping the valve to shut it or gently heating it to unfreeze it. 6) Fill gauge. This often breaks. If it is working, you can tell it is working. Reads from full to empty. The only reliable (infallible, actually) way to know how much LN you have is to weigh your tank (the empty weight of your tank is printed on the cylinder). 7) A way to move the dewar from place to place.

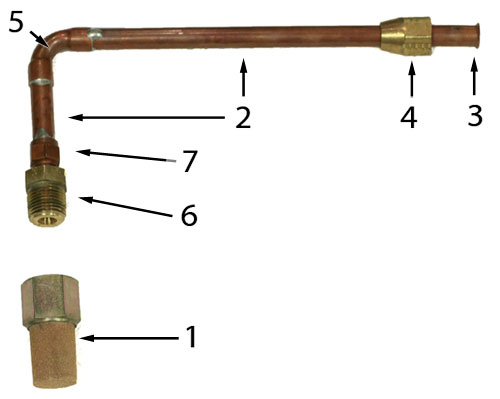

The dewar guys will try to sell you a pricey, easy-to-break liquid withdrawal hose. Forget them, and build your own liquid takeoff. All large dewars have a ½ inch flare connector on the liquid valve. Here are the parts you’ll need:

Make a DIY liquid transfer tube and save yourself some money. Here are the parts from McMaster-Carr (www.mcmaster.com). 1) If you call this a phase separator it is expensive. If you call it a muffler it is cheap. McMaster number 4450K94 ($6.14). 2) The tubing is 1/2 inch OD copper. Get it at a plumbing store. Don’t use steel. The wrong alloys are brittle at cryogenic temperatures. Sweat your connections with lead-free solder. 3) The connection to the tank is half inch 45 degree flare. You can make it yourself with a flaring tool. Remember to put the flare nut (part 4) on before you flare. If you need a flaring tool, try part number 2691A15 ($32.49). 4) Flare nut. Part number 50635K565 ($2.40). 5) 90 degree long elbow, part 5520K602 ($2.90). Parts number 7 and 8 can be adjusted. The arrangement I have is kinda kludgy. 7) Adapter, part number 5520K503 ($5.45). 8 ) Adapter, part number 4757T93 ($3.60)

Notice our inexpensive “cryogenic phase separator.” Don’t skip this part. Take a look at this dewar opened up with, and then without, the muffler:

1) With a muffler. Nice and orderly. 2) Without a muffler–crazy. 3) Another angle. Notice the flying droplets of LN in the upper left, bouncing out of the bain and spraying everywhere. Look out.

Here is the owner’s manual for the large dewars.

IV. Some Applications—the Fun Part:

Remember: these are basic techniques. No one is taking any credit. See the first paragraph of this primer.

Ice Cream:

LN ice cream is typically made in a Kitchen-Aid with a paddle attachment. Don’t use the whisk. All the mixer is really doing is stirring the LN into the mixture, not providing aeration. LN boils violently, so it provides both aeration and freezing. But the LN also floats—so without the mixer you will use a ton of LN and just freeze the surface. A liter of ice cream base at refrigerator temperature will take roughly a liter of LN to make ice cream. Turn the mixer on medium speed and add the LN slowly to prevent splashing. LN fog will be everywhere, and you will see nothing. Wait for the fog to disperse. Scrape down the sides of the bowl with a stiff metal spatula. If the mix is too soft, add more LN. If the mix is too hard or has hard lumps mixed with soft parts, turn the mixer on high for a bit to even out the texture.

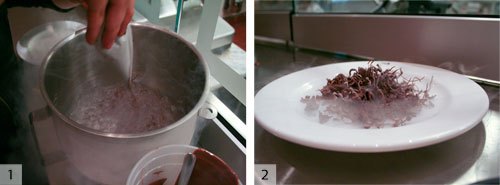

LN ice cream takes about equal parts ice cream base and LN. 1) you won’t be able to see anything. 2) The finished product.

Chilling Drinks and Other Liquids:

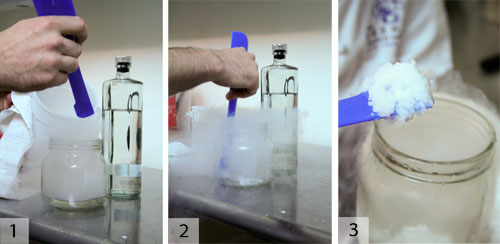

LN is a fabulous way to chill liquids without diluting them. Here is the simple rule: always add your liquid to LN rather than the other way around. LN floats. If you pour LN on top of a drink you will get a frozen layer on top with a warm layer on the bottom, and will use far more LN than necessary.

Chilling Liquids. 1) Start with LN and pour your liquid into it. 2) Stir vigorously till the fog dissipates. 3) Voila!

It doesn’t make sense to chill individual drinks with LN. It is very easy to overshoot when chilling small quantities, and you’ll freeze your liquid solid. LN is a great way to chill a lot of drinks—it’s as fast to chill 100 as 1. If you freeze your drink too solid, the heat from your hands, a torch, or hot water on the outside of the container can bring it back. Alcoholic drinks melt pretty quickly.

So How Frozen Should I Make My Drinks?

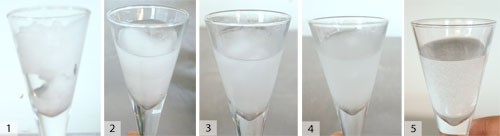

You need to be sure you aren’t going to freeze any tongues. Just because you can freeze vodka solid doesn’t mean you should. Straight liquor shouldn’t be served below -20°C (-18°C is better, a -20°C drink has a sting to it). The higher the water content, the more cold punch it will pack. A -10°C drink at 17% alcohol will taste a lot colder than a -10°C drink at 40% alcohol. Here is a visual guide:

1) Frozen. Too dang cold. 2) Starting to melt but still too cold to drink. If it will be several minutes before the drink will be consumed and you have many to serve, this texture is OK. It is, however, gloppy and thus hard to pour. 3) Way too frozen for a stiff or straight drink, this slightly slushy texture might be ok for a lower proof mix—a ballsy frozen margarita (a lower proof mix will be slushy at a much higher temperature than a straight drink, even though a straight drink will taste warmer than a diluted one at the same temperature). This texture is easy to pour and is perfect for a drink that will be sitting around a couple of minutes before service. 4) The drink is mostly thawed but has some crystals still floating in it. This is great for the many mixed drinks that can tolerate real chilling, but it’s not for flavors that are muted by the extreme cold. This texture is still too cold for straight vodka shots. If this were a straight shot the temp would be roughly -24°C. 5) The drink is syrupy but completely thawed. The perfect straight gin or vodka shot. Good for many mixed drinks as well.

By the way: you can use LN to freeze Pacojet containers in under a half hour, including tempering—but I shouldn’t print the technique because I’m sure it will void your warranty, and I don’t want all those broken Pacojet blades on my conscience.

Chilling Glasses:

LN is the best way to chill glasses, and it costs less than 10 cents a glass. I love this technique. The inside of the glass is chilled, but the stem and the base remain condensation-free and the outside of the glass doesn’t get so cold that your lips stick. To look badass, chill at least two glasses, one in each hand, simultaneously.

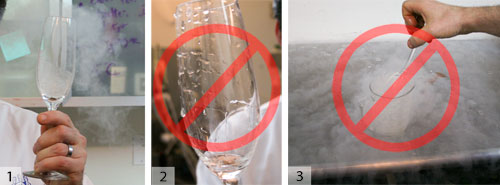

Chilling glasses. 1) Use a dry glass. Pour LN into the glass and swirl it around for a few seconds. Pour the excess into the next glass (efficient) or throw it on the floor (fun). I have never had a glass break this way and I have chilled thousands. 2) Never use a wet glass. 3) Especially never dip a wet glass into LN. Breakage very likely. Dipping the glass also super-chills the outside, which might hurt the drinker’s lip.

This technique works well with champagne flutes, highballs, rocks glasses, etc. Don’t use this trick with a martini glass; as you swirl you will send LN spraying into your face.

Blowing Smoke:

You cannot eat high-moisture foods right when they come out of LN. They will freeze to your tongue and cause you great pain. Low moisture foods—like dry meringues, marshmallows, some cookies, some cakes—don’t transfer a lot of energy from your tongue, so you can eat them almost right out of the LN. Added bonus: when you crunch these foods in your mouth, a plume of scented (and harmless) nitrogen fog shoots out of your nose and mouth.

Breaking Things Up: Raspberries, Citrus, and Powdered Fresh Herbs:

Things frozen in LN tend to get brittle. Use this fact to your advantage, as in the following three techniques:

Breaking raspberries apart. 1) Put some raspberries in LN (make sure you have enough). 2) Wait for the violent boiling to stop—now the berries are frozen all the way through. You can freeze them less if you like, but hard freezing gives you a long working time. 3) Smash the berries with a rolling pin. 4) Strain.

Raspberries before and after they thaw. Don’t try to eat them before they thaw out, but make sure you plate them while they are still solid. The melted ones are fragile.

The same technique can be done with citrus. 1) Freeze supremes of citrus solid with LN. 2) Smash. 3) Spread out and wait to thaw.

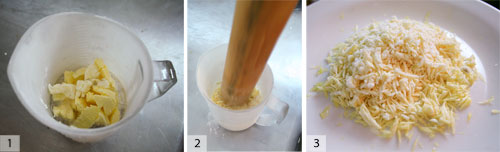

Powdered fresh herbs. This technique gives you a powder as fine as any dried herb, but with fresh. It looks great, smells great, and tastes great. It is the best way to evenly apply a mixture of herbs. 1) blanch your herbs in boiling water or they will turn black. Squeeze out extra water. 2) Fill a Vita-Prep pitcher at least halfway with LN. The large pitchers with the wet blades don’t work well for this because product sprays everywhere. The smaller pitcher with the dry blade never causes problems. Put your herbs in the pitcher and let them freeze. 3) Cover and blend, slowly working your way up to high speed. Don’t wait too long to turn on the blender after you’ve added LN or the bearings will make an awful noise. 4) Pour the mix through a chinois into a bain. 5) The stuff that is left in the chinois is too coarse for us. Put it back in the pitcher for the next round. 6) Pour the mixture in the bain through a coffee filter. This is the good stuff. 7) Put the powder in a chinois and tap it onto your dish—do it while the powder is still frozen. You can also fold this stuff into whipped cream, mashed potatoes, etc. Remember the flavor and aroma will increase dramatically as the herbs thaw. Don’t overdo it. 8 ) Allow to thaw.

Freezing the Un-freezable and Freezing in Cool Shapes:

Though this article is not about history and credit-bestowing, I have to make an exception here because Dani Garcia, of El Restaurante Calima in Spain, effectively owns the olive-oil process I’m about to explain. He has used LN to freeze olive oil and olive oil emulsions into more shapes and textures than you can imagine. LN-frozen oil doesn’t hurt your tongue because the oil doesn’t pack the heat wallop that water does.

The last technique I’ll show you is currently on the menu of our friend, Johnny Iuzzini of Restaurant Jean Georges. He makes chocolate squiggles and branches by piping chocolate into LN with a cornet.

This is a variation on the main idea that LN can make anything stay put by freezing it quickly. The possibilities are endless.

Let’s wrap this up. LN’s going to hook you quick. I remember seeing some Spanish chefs do a demo in 2004. I noted to myself that they used liquid nitrogen like it was water, whereas I was rationing it like wine. Now that I have the big tank, I rip though it just like they do. And you will too.