posted by Dave Arnold

Ike-Jime aka Spinal Cord Destruction (SCD): a Japanese fish killing technique where the spinal cord and blood vessels are severed at the head and tail, a needle is threaded through the spinal column to destroy the spinal cord, and the fish is placed in water to bleed out.

It’s unsettling but effective, as we have seen in our previous posts (here and here). The theory is that even after the brain is destroyed, the spinal cord itself sends messages to the muscles to contract. The more these messages get sent, the faster and harder rigor mortis sets in, damaging texture. If you disable the spinal cord, you stop the messages. The muscles don’t contract as much or as hard. Rigor mortis happens slower and more gently, which allows a good firm texture in the fish when served. See the bottom of this post for links to scientific journals if you’re itching for more.

Our reading on slaughtering practices across animal species makes one fact clear: what is least traumatic to the animal is best for the meat.  Improving meat quality  makes good business sense, especially when it doesn’t increase costs. So industry has adopted some techniques to reduce stress at slaughter. In fish this includes anesthesia: carbon dioxide, extremely cold water, or chemicals (one brand-name is Aqui-S – even merchants of death can have a sense of humor).

We tested carbon dioxide anesthesia on farm-raised eels purchased at Hong Kong supermarket here in Chinatown. It worked well:

We iced the eels’  water to slow them down, and then bubbled in CO2. They stopped swimming and went totally relaxed, and stayed relaxed when we handled and slaughtered them. We considered this experiment a great success. Unfortunately, the eel tasted like crap. It wasn’t the C02’s fault. The eel we killed normally also tasted like crap, with a bitter, poison-like aftertaste — maybe the eel-feces water they had been living in at the store was to blame.

I did some more reading on CO2. Turns out most fish don’t act like our eel. Most fish freak out a little before the anesthesia kicks in, which would most likely ruin our result. We decided to test it.

We also have N2O (laughing gas). It wouldn’t be feasible to use it industrially, but we figured it might be the best way to make the fish mellow and happy before being dispatched. We decided to test that, too.

In our previous Ike Jime test with Chef Suzuki, we had a tough time getting the needle through the spinal column of the small fish. We had an idea - instead of using the needle, why not fillet the fish right away? If we cut off the fillet instantly it would no longer receive messages from the spinal cord. Nils and I had also read some papers that indicated it might be a good idea to fillet salmon pre-rigor. When the fish muscles go into rigor on a whole fish, the bone structure strongly resists contraction. This force can damage muscle tissue and lead to softer meat with more drip loss and gaps between the fibers. Fillets cut off the bone before rigor-mortis aren’t restricted. They contract more than their whole-fish counterparts, but keep a nice firm texture with no gaping and less drip loss. On fish, unlike steak, firmer is better. OK, something else to test.

Two other problems with our Suzuki experiment: we didn’t wait long enough before we ate the fish, so rigor hadn’t resolved, and we didn’t test cooked meat- just raw. More tests!

The Test of Seven Fishes:

We went back to Hong Kong Supermarket with two buckets, filled them with bass-tank water, and bought seven small live farmed stripers. They looked pretty good – the guy said they had come in that morning.

We came back to the FCI and prepared them 7 ways:

1: Stressed. In our Suzuki test the fish was really, really stressed. This one was a little less so- instead of hitting it in the head with a mallet we killed it instantly by slicing into its brain- more humane.

2: Japanese-bled

3: Ike Jime (Spinal Cord Destruction). Note: I noticed that one of the fillets on this fish had a soft spot even while it was alive –like someone had gripped it hard with their thumb. The rest of the fish seemed fine.

4: Japanese-bled then immediately filleted.

5: No bleeding, immediate filleting

6: CO2 and iced sea-water anesthesia followed by Japanese-bleeding and immediate filleting. This fish, unlike the eel, thrashed around a lot when the CO2 was bubbling in the water. After about three minutes it was knocked out and stayed knocked out.

7: N2O (laughing gas) and iced sea-water anesthesia followed by Japanese-bleeding and immediate filleting. This fish thrashed less than the CO2 fish, but woke up quickly when it was removed from the bucket. We used the N2O three times. The process wasn’t as trauma-free as we had hoped.

We put the fish in the fridge and tasted them raw and cooked at 24 hours and 48 hours post-mortem.

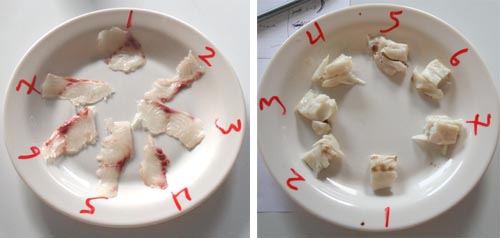

Each fish yielded two fillets. On both days, one fillet from each fish was divided into two pieces. One piece was sliced for sashimi. The other piece was placed in a zip-lock freezer bag with a cap-full of grape-seed oil and cooked in an immersion circulator for 25 minutes at 57C (135F).

Results:

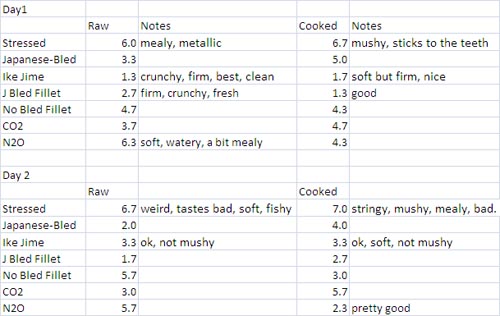

Chef Jeremie Tomczak, Nils, and I tasted the fish blind. Here are the averaged results. Ratings are from 1 to 7, 7 being worst:

In General:

There was less difference between the fish when they were cooked versus raw but there was still a noticeable difference, especially on day 1. The differences between the fish were greater on day 1 than on day 2. We had a really tough time picking out differences on day 2 cooked.

In Particular:

We all hated the taste and texture of stressed fish, every time. What does this tell us? Almost anything you can do to reduce the pre-slaughter stress on a fish is a good idea.

On day 1 Ike Jime clearly won. On day 2 it was middle of the pack. I suspect that the bruised fillet might have had something to do with this. The performance on day 1 really surprised us. We thought the immediate fillets would win or at least tie with Ike Jime, but Ike Jime had us beat. The Japanese bled fillet did well, but not well enough. Perhaps speed is the key –it is faster to do Ike Jime than to fillet. However, on small fish where Ike Jime is difficult, I think we could recommend Japanese bleed followed by immediate filleting.

The anesthesia failed. The N2O was particularly bad on day 1. Perhaps the thrashing about during anesthesia destroyed any positive effect we would have gotten. Perhaps the ice was a bad idea. We were unhappy this didn’t give a better result. We can’t recommend it for striped bass.

Science Papers:

Big shout-out to Esteban and Dave for finding this! The articles in English on Spinal Cord Destruction (Ike Jime) from the Japanese Fisheries Science Journal are available free online.

Trials for keep the fish muscle quality during chilled storage, MASASHI ANDO,et al, 2002

Brilliant! Thanks for doing the leg work! Heading to Hatteras to catch some fish and experiment!

Ike Jime seems to be the best choice, based on time constraints. Thanks for the info!

Are you going to perform this experiment again to see if you can replicate your own results?

So the nitrous fish was the Day 2 cooked winner. Any explanation for that?

Clearly more experimentation is in order, with more species of fish. Are you planning to do more rounds?

I’m curious to know how chicken jime would work too.

A possibly relevant paper emerged very recently in Food chemistry: Muscle structure responses and lysosomal cathepsins B and L in farmed Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) pre- and post-rigor fillets exposed to short and long-term crowding stress.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.05.028

Hey Dave, I love this write-up on fish assassination. Its something I would love to see in person. I have a couple of questions though. Im wondering if the Japanese bleeding and then immediate filleting is the best/easiest (not all of us have sharpened piano wire) way to get the best flavor. It clearly challenges the Ike Jime method if not matches it in taste. I know you said that the filet that had a soft spot on it probably accounts for the taste but how much better would it have done? Lastly, the cutting of the spine and vessels at the head and tail of the fish are the first two steps, but I wonder what changes occur in the meat between the two methods since the brain and nerves are already disconnected from the body. Also did you try cooking any of the fish whole and not filleted?

Also why not completely cut off the head and tail, bleed out, then fillet? Are they merely there for something to hold while filleting?

Howdy Tom,

the tail is left on as handle. The head is, I think, mainly for presentation purposes.

Gotcha. I also can’t help but think that the most defined results would be in a fish like a blue or a tuna although there’s a fat chance you’ll get a live tuna to Ike Jime.

2 interesting articles on this…

http://www.fair-fish.ch/files/pdf/english/methods-effects_en.pdf

http://www.spc.int/coastfish/Fishing/Deep_E/DBF5.pdf

Neither say to put wire down the spine. They say to spike the brain. “When the brain has been successfully spiked the mouth opens, the fins flair, and the tail flaps”…Gruesome!

Tom RE you dont need piano wire actually a piece of trolling wire 40# test we used to catch the stripers works.We use a piece of 100# mono leader material will work as well if fish is flat it will slide right up the spinal cord

Since different fish enter rigor and rejuvenate at different times, is there any way to tell the optimal time to eat after ike jime-ing them ( i.e. the striper here was best after 24 hours, where I saw somewhere else that blackfish was best after 48 hours)? Is this a trial and error thing?

Hey Paul,

Unfortunately it is trial and error. Usually, big or strong fish take longer to come out of rigor.

Aloha Paul,

Thanks for a great website. So much useful information – just a great read!

I fish regularly out of Hilo, on the Big Island of Hawaii. In general I’ve been taught by my Hawaiian mother-in-law to always ice and whenever possible bleed fish as soon as they’re caught. There is a very noticeable difference (positive) in terms of the keeping quality, flavor and texture of fish that are treated that way.

Locally there has been quite a change in the way some commercial fishermen treat their catch over time. Those who actively court the Japanese buyers do take the trouble to properly kill and store their catch. Others just throw stuff in the cooler and hope for the best…

We eat a lot of the fish I catch raw or slightly marinated. I’ve noticed that different species of fish have textures which change differently over time. Some must be eaten within 24 hours (tuna, rainbow runners) and others need to wait a couple of days (snappers) before they’re not “tough” any more. For some which are relatively flavorless and more durable (hotel food), it doesn’t seem to matter so much (mahimahi, ono).

So much to learn…

At last nights dinner in Tokyo I asked the chef if he used Ike Jime on the grilled red snapper he was serving. He said he would not do that on all fish and not for grilling. He mentioned that the grilled snapper was “no jime” and if I understood correct they fill a container with lots of ice and little “salt/seawater” and “slap” the fish onto the ice to kill it, then slide it into the tank for a bit.

He did not speak much english, and used a little translator pocket computer so I might be off

Howdy JK,

Dave Chang just told me that the best sushi restaurant he’s ever been to (I think in Tokyo, but might have been Kyoto), did not use Ike Jime on his anago. The reason? He didn’t want such a firm eel. With many types of fish (blackfish, for instance), no-jime (or western as we call it), is generally preferred on the first day (it comes out of rigor faster, etc). I think the technique used on a particular fish is determined by:

Chef’s tastes and prejudices

Type of fish

Projected time between killing and eating

Exact texture desired

Any thoughts?