posted by Dave Arnold  Â

This is our second post on the benefits and pitfalls of pressure cooking stocks. See the first post here.  Â

We recently bought a fancy new pressure cooker [/caption]

[/caption]

A Brief Recap Â

The right pressure cookers [/caption]

[/caption]

It seems like pressure cooked stock should always beat traditional stock because:Â

- There isn’t much turbulence inside a pressure cooker, so cloudiness is reduced.

- Higher extraction temperatures extract flavor more completely.

- Higher temperatures encourage more delicious “high temp flavors,” such as the meaty flavors caused by increased protein breakdown.

- The sealed pressure cooker should preserve volatiles.

Why venting pressure cookers underperform is still a mystery to me. But they always do.

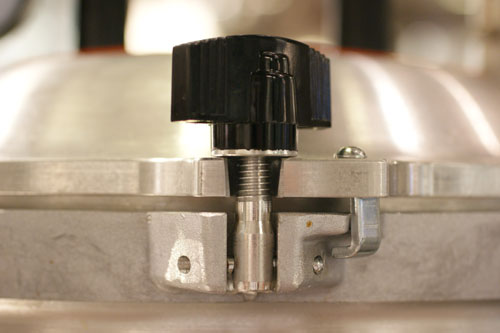

A Note on our New Pressure Cooker

The Wisconsin Aluminum Foundry Company (WAFCO) has been making the “All American” line of pressure canners since 1930. Their pressure canners are made entirely of aluminum and are usually big (up to 41 quarts). Pressure canners are designed primarily to sterilize jars and cans for home canning—not to cook in. The standard pressure canner regulates pressure with an adjustible weight, so once working pressure is reached, it vents steam—bad. You can make the weight heavier and use the very nice and accurate gauge to regulate pressure up to about 18 or 19 psi without venting, but to really go high-pressure you want a pressure sterilizer. Pressure sterilizers are used by dentists and tattoo artists; they are basically inexpensive autoclaves. Our WAFCO canner converts to a sterilizer just by changing out the lid.  We have the 25 quart stovetop model. Â

The pressure sterilizer will not vent steam unless you release the valve or take the unit above 24.5 psi. It is dead quiet. A regular pressure cooker at 15 psi reaches 250° F (121° C). My pressure sterilizer running at 24.5 psi reaches 266° F (130 ° C).  Â

The 25 quart pot heats rather slowly, and it takes a while to get the hang of regulating pressure by adjusting the gas—I plan to build a temperature regulator soon. Be careful with the sterilizer. It has a tube on the bottom of the lid. If that tube goes under the surface of your cooking liquid, the vent valve will spray hot liquid when opened. In these tests we cooked our food in stainless bains that we put inside the pressure sterilizer. Â

One quirky feature of these pots: they have a metal-on-metal seal, with no rubber gasket.  Â

Test Number 1, Changing Pressures  Â

We ran this test on previously prepared stocks so we could eliminate ingredient variables.  The tests discussed in our first pressure post indicate that pressure cooking a previously prepared stock produces similar results to creating a stock entirely in the pressure cooker.  We treated white chicken stock and brown veal stock in five different ways, as follows:  Â

- Heat briefly on the stove (control 1).

- Pressure cook in a venting pressure cooker at 15 psi for 30 minutes (control 2).

- Pressure cook at 15 psi for 30 minutes.

- Pressure cook at 20 psi for 30 minutes.

- Pressure cook at 24 psi for 30 minutes.

You can see that higher pressures = browner color. Chicken and veal stocks reacted similarly at the same pressures, so I’ll discuss them together. Confirming our previous results, stovetop was better than 15 psi vented, but not as good as 15 psi. The aroma of 15 psi vented was superior to both stovetop and 15 psi unvented—bizzare. 20 psi had a good aroma, some thought better than 15 psi unvented, but its taste was muted. The 24 psi stock was the brownest by far, but smelled and tasted dead. We need to run tests between 0 and 15 psi to determine optimum pressure. Â

Result:  15 psi non-vented chicken and veal stocks were the winners. Â

Test Number 2, Adding Lye:Â Â Â

This one gets a little weird. Friend of the blog and pro-chemist Schinderhannes suggested that we try to increase the meaty flavor of stocks by disrupting the proteins with a strong base (like sodium hydroxide, also known as lye), pressure cooking them, and neutralizing the base with a strong acid (like hydrochloric acid).  Don’t get freaked out, we aren’t serving this to people—it was just a test. Â

There’s something very appealing about Shinderhannes’ proposal.  Lye ( NaOH) + Hydrochloric acid (HCl) combine to make water and table salt (H2O and NaCl). The trick to not poisoning people is neutralizing the lye. Â

We don’t have access to high grade lye, so we used this:Â Â

Don’t use this stuff. I don’t want to hear about you getting hurt. Eating only a small crystal will do severe, irreparable damage to your insides. My doctor mom used to tell me horror stories of kids who came into the ER after eating drain cleaner. Anyway, we prepared two identical batches of chicken meat and water, added some 33% lye solution to one (we added 0.5% by weight NaOH to the stock), and pressure cooked them both for 45 minutes in a non-venting pressure cooker at 15 psi. Here is what they looked like: Â

The difference is pretty plain. The lye stock is still poisonous at this point so we need to add hydrochloric acid to neutralize it. Problem is, I can’t get pure hydrochloric acid, so I went to the hardware store for muriatic acid, which is fairly concentrated HCl, used to clean tiles. We added enough HCl to get a neutral reading on our pH meter. Look what happened: Â

Whoa! The stock turned white and clouded up. I tasted it to make sure it wasn’t poison. It wasn’t. Then we figured out how much salt to add to the normal stock to match the salt created in the lye stock acid base reaction. Â

Here is Nastassia tasting them blind. Â

Well, the normal stock won. The lye stock tasted a little weird. The next day the lye stock looked even stranger:  Â

The stock on day 2 smelled and tasted strongly of lye. I’m  guessing the lye was trapped in the precipitate that formed when we added the acid, and it leached out overnight. The lye taste was still present after we got rid of the cloudy stuff in our centrifuge.Â

All in all, not a ready-for-prime-time technique, but a fun experiment.

Very cool. As a home cook with one of those infernal venting pressure cookers, I’ll be interested in your experiments with lower pressures. It’s easy enough to get half an hour of sub-15 psi cooking with one of those. Just slowly bring the pot up to pressure, and when it just starts to vent, turn off the heat and let it sit at 245 (and slowly falling) for half an hour until it hits 212 and releases pressure. If that technique makes a better white chicken stock than the toss-everything-in-the-oven at 190 F for 8 hours technique, that’ll be worth doing.

Actually, now that I think of it, you could also bring the pressure cooker up just to venting, then put it in the oven set to 240 to get an arbitrarily long high-pressure period!

Great post. One quick thought on the vented vs. non-vented 15psi aroma difference. The vented cooker will allow atmospheric oxygen to be purged from the chamber whereas the non-vented cooker will retain the O2. This could oxidize some of the aroma compounds or encourage molecular condensation of small organic compounds reducing their volatility. Some pressure cookers (like Fissler) allow the chamber to purge before the desired pressure is reached at which point this purge valve is sealed with positive pressure from the chamber and the venting is ceased.

Interesting Patrick,

I’d like to test that theory.

I can’t tell you how much I love this article. Great stuff but please also try if possible to give a recommendation amongst the more readily available domestic pressure cookers.

Line of the day – “I tasted it to make sure it wasn’t poison. ” Priceless…

Keep up the good work.

Hi Joesan,

If you have the money and don’t need huge volume I’d go with Kuhn Rikon.

Unless you adjusted the pH of the salted stock to 7, the deadness of flavor might simply be from not ENOUGH acid or base. I dont think much of what we eat is perfectly neutral, and physiological pH is more like 7.4 (slightly basic). I’m sure you’ve also added vinegar to perk the flavor of something up before, and you’re certainly changing the pH there.

I can think of two better experimental designs:

one would have been to test the pH of the control stock, and then adjust the experimental stock’s pH to that level, before adding NaCl to the control stock (because NaCl is basic and will not affect the pH)

much simpler (and better, actually, but i’ve already typed the previous one out) would be to use a quantity of HCl that is equimolar to the amount of NaOH you added. This would convert all of the NaOH into NaCl without affecting the pH.

(I also have to say that I don’t think this is going to do a whole lot, but I could be wrong)

Another source of your off flavors might be the fact that aluminum doesnt like highly basic or highly acidic things. you might have gotten some Aluminum oxides into your stock or something. stainless steel would probably handle this better than the aluminum of the all-american (I have one too)

You also might want to try finding a different base or buffer system.

Howdy Rageahol,

I should have been more accurate in my post. We did measure the pH of the initial stock (low 6’s) and adjusted the lye stock to match.

The problem with pre-measured HCL is that the NaOH is added to a water+chicken meat system. Since we are discarding the chicken meat we have no way to know how much NaOH is in the chicken meat vs the liquid, so we have to titrate. What we could do is add lye, pressure cook, add HCl, pressure cook, strain and adjust. Might be better.

The stock never touched the aluminum. We could our stocks in stainless containers inside the pressure sterilizer.

Dave,

I’m wondering if you can expand on this a bit. How does it work, exactly, to cook the stock in a stainless container inside the big aluminum WAFCO pressure cooker? How do you do it?

Presumably, cooking in a stainless container inside the pressure cooker reduces the capacity considerably. Considering that most stocks probably aren’t all that acidic, is there any particular reason, if one wants to make a big batch of stock, not to cook the stock directly in the WAFCO pressure canner?

– Sam

My memory is that we wanted to remove any idea that the aluminum might react with the stock. You just add water to the bottom of the WAFCO and put the bain maries on trivets inside. It does reduce the capacity. BTW, one of the coolest ideas in modernist cuisine is doing stocks/etc in canning jars in the pc. using jars reduces you capacity considerably, but your stuff is sterilized and you don’t have to worry about the venting problem (the jars are sealed).

Regarding venting in cans in the PC, isn’t it the case that the cans still vent as the liquid in the cans boils off? That’s why the cans seal when they cool, right?

I spoke to Chris Young about this briefly. When you are canning for canning’s sake, I believe you leave the lids loose. If you were going for non venting, you’d have to pre-tighten the lids. In this case you should only use natural pressure release and you might not be able to trust the sterilization. People who use canners as sterilizers are very careful about venting steam from the unit prior to sealing to remove dry air from the unit before. The theory is that dry ai can remain in pockets and prevent total sterilization. Don’t know if that is true. I’m sure that in canning you can get around this by cooking a bit longer (but I don’t have data). You won’t get the vacuum seal as confirmation of a good job done.

Is it possible that the mix of heat, fat, and lye resulted in saponification and that the mystery precipitate is the product?

Howdy Frank,

Dunno.

Hi Dave,

you´re my man!

Thanx for trying this and I am awefully sorry it din´t quite work out.

I bet you´d need like several interns and a lot of experiments to figure out if this can have any benefit if dosed properly. Don´t do it!

This one data point clearly indicates that there seems to be a limit ot the protein hydrolysis you should have in a stock.

BTW the browning is not surprising at all it is well known that maillard is faster at high pH.

When at the end of your fist paragraph you stated my crazy proposal was a doozy I got all excited. My limited knowledge of American slang (which obviously changes over time) led me to the initial conclusion that this would be a breakthru discovery and we would became famous toghether 🙁

Did I ever mention that the succes rate of my crazy ideas is extremely low? LOL

TTFN

Hannes

One more very quick comment from the village idiot who claims to be a chemist!

I was only focused on the proteins, but you seem to have some fat in there as well:

Now fat is the tri-ester of glycerine with three fatty acids.

What happens now is you saponify the fat with the lye to get free glycerin and soap! (This is exactly how soap (the sodium salt of fatty acids) is beeing made industrially….)

So even after neutralizing the strong base you now have free fatty acids and glycerine and thus your stock will taste soapy.

Sorry for not getting this earlier….

Hannes

Hi Dave,

one more thing before I admit total defeat:

I checked on Justus von Liebigs original recipe (a bitch to find) he used a very small amount 32 drops of conc HCl per liter – more or less 1.5 ml per liter – with 1kg of very lean meat or chicken cut into small pieces.

Anyways it seems the way to go is first acid then some base (Liebig actually skipped the neutralisation step…)

Still prolly not worth a try, specially since HCl does eat stainless for lunch 🙂

Doe some other funky stuff instead!

Hannes

Howdy Schinderhannes,

You know, I was thinking about acid. Acid would actually inhibit browning reactions leading to a blonder stock. I wonder if a small amount of a normal acid (like citric) might affect stock in some interesting way?

Off topic but something I’m thinking about:

We’ve been working a lot on torch-taste recently. I am convinced torch taste is due to the thiols added to make the fuel stink. We have butane from lighters with a very low (to my nose) thiol concentration and they have no torch taste. Out propane has loads of thiols and a distinct torch taste. I can reduce the torch taste of the propane by slowing the flame down (increasing thiol combustion?), or by slamming the flame into mesh.

Some questions that have come up:

Why don’t you smell airborn sulfur oxides when burning the thiols in fuel? is it just that thiol concentration is so low and the smell so repellant?

Why do starches without fat pick up less torch taste than medium fatty mixed foods (like cheese rinds)?

Also, using thiol rich fuel to burn the outside of a raw egg makes nasty nasty smells on the inside of the shell when cracked, whereas low thiol fuels don’t. Something about the alkaline nature of egg white? Curious.

Greetings earthling,

Thou pose many and difficult questions.

The chemical reactions going on in a flame are extremely complex radical reactions and hard to follow. Many variables hard to control like oxygen to fuel ratio, temp, turbulences etc.. Analytics are a nightmare.

As you know depending on the way you use a torch you can e.g. generate soot or not.

Soot is basically graphite and some smaller polyaromatic hydrocarbon species magically generated from propane, an alkane. Don’t ask me how, LOL (impossible to explain in text without drawings to say the least.).

I do believe that these higher hydrocarbons are one main part of the stench. So as long as you can make the flam burn clean (e.g. low flame) you will be off a lot better.

Now the sulfur comes into play: sulfur compounds with low valent sulfur (only carbon or hydrogen attached to the sulfur) are know to be the most horrible and reeking substances of them all, chemists hate to work with them. Their odor threshold is extremely low. So minute quantities of these are smellable and the amount in gas is measure in ppm or ppb. Normally ethyl mercaptan or tetrahydrothiophene are used as odorizers, but it don’t really matter what you use. Sulfur dioxide is many orders of magnitude less smelly. You can smell it when lighting a match but this is a bazillion times more than the SO2 you get out of burning gas with an odorizer.

Now let’s consider incomplete combustion with the thiols on board: this might also lead to sulfur containing higher hydrocarbons that cause some awful smell and taste.

On the other hand sulfur is oxidized pretty easily and I am not really sure if one can find low valent sulfur species in combustion gases, but this is pure speculation.

To sum it up: we certainly have some freaking aromatic hydrocarbons which would cause a typical fuel taste plus maybe some similar compounds with the added sulfur kick in em.

Both would be very lipophilic and love to go into anything containing fat but be a lot more reluctant to condense onto starch. So this is pretty straight forward.

The rough surface of the egg can also cause our mystery compounds to condense on it very nicely and than they penetrate the egg.

Regarding the sulfur you could do some controls to see if the original thiol is causing the off taste. You could blow the not ignited torch into some neutral veggie oil or onto a fat impregnated paper towel, and see what you can pick up in smell and taste. If this is what you sensed earlier it is clear you are correct and it is said sulfur compound. If it has a different taste, we are back to speculation.

I know you usually take a lot of care to control all variables but nevertheless let me ask you the following to challenge your observation that low and high thiol fuels behave differently:

Did you use the same burner with the same nozzle and the same flame size etc?

Or was one a hand held little burner like for crème brullé and the other an industrial flame thrower normally used to tar a roof?

If they were the same I´ll go with your hypothesis, otherwise I´d say it is the different flame characteristics that cause different amounts of soot and higher hydrocarbons to form.

If I was U, I’d use my considerable engineering skill pair with my lack a fear to try and design my own flame thrower based on something that burns notoriously clean like alcohol. I proposed abusing a MSR Whisperlite or some similar camping cooker initially designed for white fuel as a possible starting point for this ghetto flame thrower in some earlier post.

Keep us posted on the results of you tests!

TTFN

Schinderhannes

P.S.: on the acid issue for your stock: citric might be good to stop Maillard rx. And to keep white stocks white, but it will be a little to weak to speed up the hydrolysis of you meat considerably. For this I have a new proposal: how bout phosphoric acid: it’s not reacting with stainless (it is used to inertize steel), it is non toxic (think Coke) not volatile (good for the aluminum autoclave) and pretty strong……

Schinderhannes,

Thanks for the info: I am currently digesting this comment.

I’ve found that with a MAPP torch, I can detect no torch flavor. I wonder if its a low thiol fuel, or if the higher combustion temperature gives a more complete combustion.

Good lord man. I’ve previously suspected you guys are madder than a hatter but this clearly proves it! I once ate orange-colored tempeh brought home from the lab by a UC Berkeley biochem grad student. But nothing would persuade me to try a glass of plumber’s lye + muriatic acid dosed stock.

I know it. It is a real “don’t do at home” sort of thing.

I’m with michael above. You guys are nuts! But I can’t make myself look away. I think I have read that industrial grade lye is produced using mercury. You probably know that food grade NaOH is used as a wash on traditional German pretzels. You couldn’t get it from a bakery supply there? Sheesh, next time, you can send me an email and I’ll get you some from the Apotheke here. Also, CaOH (lime) is used for nixtamalization of corn to make fresh masa and hominy. Surely someone in NYC is making fresh masa tortillas?

I used to make long-simmered stock (chicken, generally), but then I moved to a country where electric stoves are de rigeur and electricity costs about 4 times as much as in the US. I started pressure cooking my stock, but I always finish it with an hour stove-top simmer. I feel like the flavor develops during the stove top simmer, but I haven’t actually conducted any blind taste tests to that end. It just seemed wrong somehow to expect the pressure cooker to have the same result as an 8 hour simmer…now I am rethinking my entire process. (Though a wood stove is in our near future, in which case I may return to the 8 hour simmer. Very rustic, I know.)

Howdy Kelly,

I had not heard about the mercury. Ouch. Our baking department uses soda for their pretzels so we don’t have any lye. I have always wanted to do nixtamalization but have never got around to playing with it. I wonder what would happen if we nixtamalized wheat or rye? Someday I’ll try. I have never seen lime for sale in a Mexican store here, although we have both Thai red lime and white pickling lime, but I don’t know how basic they are. I’ll have to look into it.

Dave,

Don´t worry too much about the mercury, you wont turn autistic, promised. LOL

The old industiral process to make lye and chlorine gas out of salt did in fact use mercury and traces of it were in the lye, but this process in next to extinct (at least in Europe).

The new environmentally friendlier processes don´t have this problem any more.

Hannes

schinderhannes said:

“this process in next to extinct (at least in Europe).”

About a year ago, a study found mercury in several products containing high fructose corn syrup (HFCS). The source of contamination is likely from lye used in the production process. A quote from a Washington Post article about the study reads:

“The use of mercury-contaminated caustic soda in the production of HFCS is common. The contamination occurs when mercury cells are used to produce caustic soda. ”

The article can be found here:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/01/26/AR2009012601831.html

As an aside…Americans were putting lead in paint until 1978, while in most countries in Europe banned lead in residential paints more than 50 years earlier (1921-1926, depending on country). Sometimes the Americans are a bit late to the game…

First Foodgrade reagents should have been used when doing any food experimentation. A better idea if one is thinking of practical application is to use kitchen “chemicals like baking soda for alkalinityand vinegar for acidity Tasting to find out if itis toxic reminds me of an answer given by a student when asked in an organic chem exam to differentiate methyl alcohol from ethyl alcohol, answer was: if you drink the sample and your eyes bulge and you die that is methyl alcohol if not then you are sure it is ethyl alcohol!! Well the experiment is certainly interesting, though am sure a better designed method may have been done in some food science lab.

Howdy Libia,

No doubt you are correct. Baking soda and vinegar, however, don’t add to make table salt. A couple of notes: I would never serve this stuff to JQ public. I was also being a little tongue in cheek about the poison thing. I was close enough to neutral not to worry too much. The toxicities of HCL and NaOH are related to concentration. The only real concern is trace nasties in the non USP chemicals I was using. I wouldn’t do this every day and we consumed only a tiny amount –not that it is a good idea to consume them at all.

Hi Libia,

Sodium Bicarbonate and vinegar are indeed better choices if you want to play around with pH in the Kitchen. But just FYI, the food industries do use NaOH and HCl to adjust the pH in some cases.

http://www.ifsqn.com/forum/index.php?showtopic=12490&st=0&start=0

And Dave’s right. One needs to check the specifications for the amount of heavy metals and that they are within the acceptable range for food use.

for lye supplies a good way to get food grade is to look for soapmakers, have been experimenting with proteins in a basic solution and found a good supplier here : http://www.essentialdepot.com/servlet/the-2/2-lbs-Food-Grade/Detail , good luck with the experiments and keep us posted, also if you’re looking for chemicals in the future look at places like fischer scientific they do small orders for stuff like schools etc.

Wow- you and your site are insane! I love it. I’ve been reading through all your crazy posts and I’m really taken aback by the uniqueness of everything. Not sure if I’m sheltered and just unaware of this type of chemistry/cooking breed of culinary ventures, but I’ll defintely be bookmarking this one! Going to go cook a fish in oil now, thanks!

Thanks Mr. Conveyor!

I am a long time soap maker and have a little to contribute here. When you added the lye to the broth you started making soap. When you heated the broth you encouraged the chicken fat to saponify. When you added the acid to the broth it combined with unreacted lye forming salt. Salt has long been used to firm up a batch of reluctant soap. That would explain the precipitation. Letting the broth rest overnight allowed saponification to continue.

I am surprised that the broth smelled of lye the next day. I would expect a slight chemical smell, but not a lye smell since it had been neutralized. Did you test the pH again before dumping it out?

Nixtamalization may be the way to go. A little lime water could be added before pressure cooking. I’m afraid that you would still run into a clouding and precipitation problem when neutralizing the broth though. At least with lime water you would be making chalk as a byproduct instead of soap.

To elaborate on the soap idea: saponification leaves long fatty acids that are anionic on one end (polar, hydrophilic) and nonpolar (hydrophobic) on the other end. Soap itself is a salt of these, as Kevin said, in which the anionic head is paired with a cation, usually from the base used (e.g. Na+).

When these fatty acid salts are formed, the acidic solution around them is ionic and polar, which encourages the nonpolar tails of the fats to get the hell out of there, huddling together to avoid letting the polar medium touch them. This is the same way soap removes oil from your skin; the hydrophobic tails surround the oil droplets in spheres with the polar heads sticking outward (what is called a ‘micelle’ structure) allowing it to be washed away with water.

So that’s more than likely what the solids were after acidification–agglomeration of the hydrophobic fat-ends of the soap that was created after alkalinizing.

Hey guys–You need to try changing your cooking times. You should try an experiment where you change the cooking time to keep the amount of cooking the same. For every 10deg C you increase the cooking temperature, shorten the cooking by half. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arrhenius_equation

Dave, do you think it would be possible to replace the standard vent pipe on my American Pressure Cooker with the sterilizer control valve on the Sterilizer Cooker?

I guess I really should be asking American, but I’m betting they will try to sell me a whole new lid.

Thanks!

Nevermind. I think I’ll just add weight to the 3-sided weight that came with the unit. That should keep it quiet unless I overshoot 15 psi. I’ll experiment with how much weight to add.

Hi Keith,

I have both lids, but have also added weight to the 3 sided weight. It works, just make sure it is balanced well.

Thanks, Dave! I couldn’t get the weight to seal when I added more weight to it. Any tips?

Dave, sorry to keep bothering you. I still can’t get mine to seal by adding weight. I think it may be a function of the shape of the indentation of the weight, not the actual weight – which wouldn’t change because the damn thing weighs the same no matter which way it’s sitting on the steam pipe. Duh! I feel like such a fool, now. I guess my only recourse it to oder the sterilizer lid. I would prefer to just order the sterilizer regulator, though. Also, can you shorten the length of the dip tube in the sterilizer so it won’t spray hot liquid if it opens? I’ll be using this in an educational environment, so I want to be extra careful.

Thanks!

Hey Keith, remind me which cooker you are using. I have used added weight (important that the weight is centered) on my american pressure canner to increase the pressure….However: The unit will still vent if the pressure exceeds the new weight’s release pressure. What you have to do is weigh the unit down enough so it won’t vent until, let’s say, 20 psi, then visually ensure (using the gauge) that the pressure never goes that high. If memory serves, the American PC unit’s weight has three different hole sizes drilled in it and those different sizes push harder or softer on the supplied weight, so that one weight can do 3 pressures.

I would never recommend doing something drastic like installing an ASME safety valve set to 20 or 22 psi and temporarily sealing the weight vent –although I might do it myself.

So it IS a function of weight. I have the American Pressure Canner. I just couldn’t get it to completely keep steam in above 15 psi – it kept leaking. Which is why I thought it might have more to do with shape of the hole rather than the mass of the weight.

I’ll experiment more with balancing the weight.

Thanks for advice!

Congratulations! I believe you have just rediscovered the Hofmeister effect, where salt causes dissolved proteins to precipitate. I would venture to guess that you will get similar cloudiness by adding enough salt. I somehow doubt that 45 min in a pressure cooker is enough to chemically break enough peptide bonds in the protein to make that much of a difference.

Don’t you think the cloudiness is cause by some sort of saponification reaction?

Dave, curious as to how gelatinous the pressure cooker stocks were? I’d assume they wouldn’t be.

My memory is that that they are as gelatinous as regular long cooked stock. I don’t think the pressure cooker hydrolyzes too much gelatin (although it does a bang up job of breaking collagen into gelatin).

Instead of testing by psi, using a temperature probe to compare stocks with will get you more consistent results, like if you travel to a different altitude. what I mean is that instead of educated guessing a little over 15 psi as ideal you could say 251.3 degrees is ideal for stock which is more accurate.

Howdy Neil,

Non-electric pressure cookers all use pressure as their regulating mechanism because it is so much more robust and easy to do than a non-electric temperature control. The only drawback, as you say, is that you have to know the atmospheric boiling point at your current elevation.

Great (cooking) science! Thank you for all this useful information.

Does anybody here know if the Kuhn Rikon Duromatic line (somewhat cheaper)is also non-venting? Do they perform the same?

Thank you very much brothers and sisters!

Howdy. It looks to be non venting. It looks like the standard Kuhn Rikon valve –a spring-loaded plunger in the center of the lid (same as I have on mine) –they don’t vent.