by Dave Arnold

This is my second post on Kombu –the MSG laden, super-seaweed bedrock of Japanese cuisine used to make kombu dashi (seaweed stock).  Read the first one here. The first post dealt exclusively with Ma Kombu, the most popular type of seaweed used for dashi. This second post will compare varieties of Kombu, and will detail our findings that the part of the Kombu you use is as important as the type of Kombu you use. Kombu is a leaf stalk, and different parts taste different.

Japanese chefs care deeply about the quality of their Kombu –whether it is farmed or wild, whether it is harvested too young or is allowed to grow for at least two years, and where it is harvested — like all agricultural products, kombu’s quality depends on terroir.  Kombu affineurs age fine kombu for years like wine or cheese. For Ma Kombu, thick dark specimens with a white center are prized for producing the best, most aromatic dashi (see this short video for an explanation of Ma Kombu harvesting and trading). But I have yet to hear tale of a chef’s favoring the base or tip of the Kombu. Whether in Japan or the U.S. you cannot buy just the base or just the tip of the Kombu, and there seems to be no culture of preference for different parts of the leaf. Most of us just buy packages of Kombu pre- cut into strips, and we have no choice as to the parts we are getting. Badass sushi chefs order the whole Kombu leaf, so I guess they can use different parts of the leaf as they see fit — but I can’t find anyone talking about these choices.

Philosophical Preliminaries:

Books and research papers on Kombu, and chefs I have spoken with, always focus on one particular aspect of Kombu dashi: how to extract the maximum amount of umami (i.e., MSG and its relatives). I’ll be a bit heretical and say that I don’t care about that. Yes, I want to extract enough umami –that’s the primary reason to use Kombu; but extracting the maximum amount of umami shouldn’t be the goal. You can just add MSG. The goal should be extracting the best taste, and that’s what our tests focused on.

Recap of the first post:

In the first post we tested eight different techniques for making kombu dashi and discovered our favorite: vacuum bag the kombu with ice water (because liquids need to be cold to be vacuumed) and cook in a circulator at 65 C for 1 hour. The vacuum bag helps push the water into the Kombu, speeding extraction and preventing loss of precious aroma. The circulator provides accurate temperature control. Since then, we tested the temperature of extraction by making Ma Kombu dashi  with 10 grams of Kombu per liter vacuum bagged and cooked for one hour at 60â°, 65â°, 70â°, and 80â°C. The 60â° broth was weak and the 80â° was bad –65â° and 70â° were best. We chose 65â°C as our magic number. In my initial post, it appeared that pre-infusing Kombu with water in a vacuum bag might be better than bagging and cooking right away. In our tests pre-infusing the Kombu did seem make a better broth, but the effect wasn’t as great or clear cut as I had anticipated — and benefits decreased rapidly after a few hours. I’d say once you make the move to vacuum bagging, the infusion step is optional. The rest of the tests were pre-infused for 1 hour before cooking.

Yuji Shows up with the good stuff:

Our buddy Yuji Haraguchi from True World Foods secured an excellent variety of very high quality wild and farmed Kombus.

Tasting Ma and Our Leafy Revelation:

First, Yuji gave us the highest-quality Wild Ma Kombu — Shirokuchi hama ma-kombu , to be precise. Ma Kombu is the king of kombu from the frigid waters off the southern shores of Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost island. It came as one long piece, folded in half and beautiful to behold.

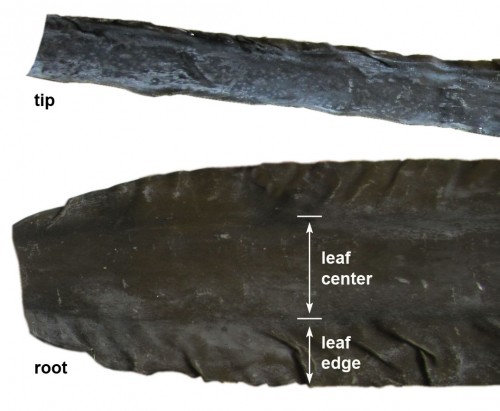

I broke off a piece near the tip of the leaf and ate it. I then tasted a piece near the root. The flavor was completely different.  We found the tip to be a lot more flavorful overall –salty sea-weedy with a bright, faintly acidic note that was absent in the thicker root-end. The root-end has two distinctly different types of flesh –the thick center part and the wavy edge. They tasted different, so we decided to test broth from all three parts. We also used the Ma Kombu to test our ideal amount of Kombu per liter of water.

Our broth tasting panel — Nils, Christina Wang (at the time our director of education), Yuji, and me – tried eight broths:

From the Tip: 10 grams of kombu per liter water made a good but weak broth. 20 grams per liter made a strong salty and sweet broth,  good but aggressive. 15 grams per liter was very well balanced. I originally preferred the 20 gram, but later decided that the 15 was, in fact, better in its own subtle way.

From the Base: 10 grams per liter was really light and weak. 15 grams per liter was also light and also weak in flavor. 20 grams per liter was very well balanced and not nearly as sea-weedy as the 20 gram per liter broth made from the tip. As a group, the broths from the base were milder than from the tips.

Both the 15-gram-per-liter tip broth and the 20-gram-per-liter base broth were balanced and good. Many Japanese recipes specify the amount of Kombu to use as a length– “use a 4 inch piece of kombu per liter of water.â€Â These recipes would, therefore, use a higher weight of thicker base Kombu per liter than thinner tip Kombu. I wonder whether that type of measurement actually helps to even out variations in broths made from different parts of the leaf.

Also From the Base: We made 10 gram per liter broths from the edge of the leaf near the base and from the center of the leaf near the base. The broth from the center of the leaf was slightly better than the broth from the edges, but the difference wasn’t drastic.

The Winner: Â Â 15 grams per liter from the tip. All other broths will be made at 15 grams per liter.

The Other Kombus:

Our Farm-raised Rishiri Kombu came from the very north of Hokkaido and smelled  like a dog that just walked out of the ocean. Eaten dry, the base had a basement/fish-pee aroma (not in a bad way) and a slightly ammoniac flavor. The tip had a chicken broth flavor that I loved –I could chew it all day. Broth made from Rishiri Kombu is light in color and is used in Japan for dishes that require colorless broths. Broth made from the base had an acidic note. Broth from the tip was better, very brothy with a pepper note –not acidic, round.

The Wild Hidaka Kombu, also from the northern shores of Hokkaido, was milder and not as refined as the ma Kombu, but we liked it dry. We detected licorice flavors in the dry stalk and thought it would make a good miso soup. In Japan, Hidaka is used often used in simmered dishes. Broth from the base was reminiscent of seaweed mixed with mustard greens. Broth from the tip was better, and had a clam-shell/shellfish note. Overall, the Hidaka broths seemed hollow and not robust.

Our Wild Naga Kombu from the south of Hokkaido had a sweetness I liked when eaten dry — I want to make a candied Kombu with it. In Japan it is often used for making Kombu-rolls (kombumaki). The broth from the tip had a chicken and carrot stock flavor that was far superior to the slimy-bodied broth we made from the base.

The Wild Rausu Kombu from the North of Hokkaido had a good meaty flavor when eaten dry. The flavor in the tips seemed to have a longer finish than that from the base; but that may have been because the base was as hard to chew as an elephant’s toenail. Rausu is popular in Japan but isn’t used in some high end preparations because its broth is darker than Ma Kombu broth. Broth from the tip had a good clean seaweed flavor and some meatiness. The base tasted like a wet dog.

Smackdown:

The favorites from each of the five tastings were pitted against each other. The broths were ninety minutes old when we re-tasted them, so their flavors might have shifted somewhat.

First: Ma Kombu tip broth was unanimously chosen as favorite. No contest. Balanced. Delicious.

Tied For Second and Third: Hidaka and Rausu tip broths. The Hidaka had a seashore taste (like I had just taken a swim and swallowed some water –I didn’t choose it second, I chose it fourth).  The Rausu  was balanced but not a robust as the Ma.

Fourth: Rishiri tip broth. It was OK, but slightly acidic.

Fifth: Naga tip broth was unanimously chosen last. It had an egg-broth taste, like it had developed some sulfur compounds.

Special Bonus! Chef Suzuki Kombu Demo:

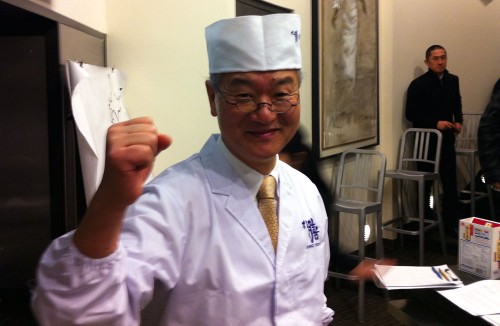

Yesterday, Toshio Suzuki, master sushi chef and our Ike Jime (Japanese fish killing) Sensei, did a kombu dashi demonstration at the FCI.

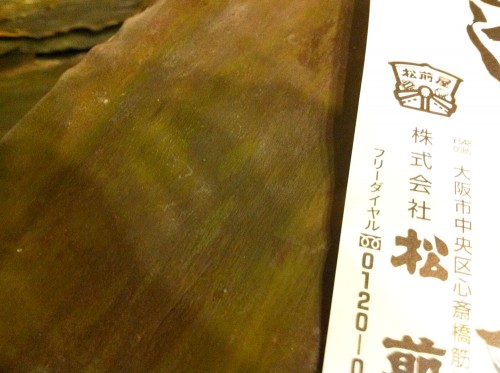

Chef Suzuki’s Kombu came from the same source  as ours, the Matsumaeya corporation, importers of fine Kombu. He demonstrated all the types of Kombu we had tested. What struck me most was his demo of ichiban (first) dashi versus niban (second) dashi. When making a full-on dashi, Kombu isn’t the only ingredient –shaved katsuobushi (dried, cured skipjack tuna, bonito) is also added. I’ve always marveled at how short an infusion time Japanese chefs use for the katsuobushi when making ichiban dashi –less than a minute. On top of that, they don’t squeeze any of the delicious liquid out of the fish flakes. Invariably, they claim that this technique yields the best tasting, most aromatic dashi for use in suimono –clear soups. The used Kombu and Katsuobuhi flakes are then used for making niban dashi, which is heated much longer to extract the rest of the flavor and umami from the base ingredients.  This secondary dashi is used for preparations like miso soup that require a stronger presence and can deal with a rougher presentation of Kombu and Kastuobushi. Until the demo, I had never really understood the link between the inchiban and niban dashis. All my dashi forays had aimed at maximum extraction of flavor in the ichiban stage –using few bonito flakes and extracting more Kombu flavor from the beginning. This precluded making a good niban dashi. Perhaps the Japanese technique really does produce the best of both worlds –a subtle ichiban dashi to enjoy unadorned and a more rough and ready niban for more robust preparations.

Chef Suzuki showed us some other cool things. Below, some kombu that has been aged for three years. Aged Ma Kombu is apparently even more bad-ass than regular Kombu. I was able to taste it dry but didn’t make dashi out of it:

Another cool product: Oboro Kombu, which is Ma Kombu that has be soaked in mirin and vinegar, then dried and shave into thin sheets. The best stuff is paper-thin pieces shaved from single kombu leaves by hand — surely a tough job. The outside shavings are dark green, like Kombu. The inside shavings are white. A lot of people prefer the white shavings for aesthetic reasons, but the green shavings taste better. Both are delicious. I will use this stuff as a garnish or topping on a zillion different things. Less fancy Oboro Kombu is made by shaving blocks of Kombu leaves that have been laminated together. Check it out:

Finally, a cool looking shaved Kombu sheet:

Did you catch what conditions the kombu was aged under?

And what happened to Nils’ leg?

Hey Colin,

He broke that a while back. The tastings were done months ago. He’s healed now. Chef Suzuki didn’t give me the aging technique.

Any online distributors, or ways to procure any of the varieties for home use?

Hi Dave,

For us home cooks, can you put kombu in a ziplock with water or do you need the chamber vac machine?

Good question Andrew,

I haven’t done the test. I’m sure it would be good, but The infusion time might become more of a necessity.

Fascinating stuff!

Should I pre-soak and vacuum my Gyokuro tea before brewing, considering that the established Japanese broth-making procedure appears to be suboptimal too?

Firstly, so very impressed with all you lot get up to. Been a fan for years now, so thanks and all that.

Really interested in your dashi research. This may have been asked on previous comments – sorry if it has – but how about the water? When I have spoken to Japanese chefs like Ischida-san and Murata-san about this, they couldn’t stress enough that the water they used was crucial, and always brought their own water with them when doing demos abroad. Are you planning on looking into this? I usually filter my water at home when making dashi, but there isn’t much else to do, I guess.

Also, on the ‘to wipe the kombu or not to wipe the kombu question’, I can never bear to wipe off all that wonderful, white glutamate, so never do…

Hi Michael,

Thanks for the compliments. I never wipe off my kombu -ever.

We haven’t tested the water. From what I hear soft water is best, and the Kyoto guys sure do love their water. I have heard NYC water is pretty good. Someday I hope to do the test.

Looks like Nils might be able to provide some insight on cooking with cannabis and taking bong hits with kombu infused bongwater. Just listened to the previous weeks Cooking Issues and to the cook inquiring about weed cookery I would recommend the Marijuana Horticulture book by Jorge Cervantes. He has a nice section on it.

Funny. Nils is also a huge reggae fan.

Thanks for the article. These kombu articles have really helped me make food that I can make for my vegetarian girlfriend (and enjoy eating myself, too).

Cool. Have you experimented augmenting with different mushrooms? I’d like to do a katsuobushi vs mushroom in kombu test for umami levels (obviously the taste wouldn’t be the same.

I usually use dried shiitakes . I use 20g/L kombu, 10 or 20g/L of shiitake depending on the application. I find that the 20g kombu, 10g shiitake combination can make a pretty credible chicken stock substitute for a lot of veggie dishes. Definitely much better than any of the commercial vegetarian/vegan stock or bouillon crap I’ve tried.

Have you ever noticed a distinct allium flavour in the kombu dashis that you’ve made? The last kombu I used had this bizarre wild garlic taste sometimes (though no allium aroma).

I haven’t, but I haven’t been looking for it.

Your Kombu post was most informative. I may have missed something in the post but i think it should be mentioned about the water to be used for the Kombu. The Kyoto chefs that I have worked with have mentioned to me countless times it is useless to use Rishiri, or any other Kombus if you do not use a very soft water. The amino acid and flavor extraction is nothing if a hard mineral water is used. they specify this all the time, especially with Rishiri use, their Grand Cru kombu of choice. Unless I am missing something, the control of the different tastes of kombu, their maximum potential, is unrealized unless the water used is considered; which they will tell you is really the most significant factor in any multifaceted dashi based preparation.

Howdy David,

I have read the same thing you just mentioned and have also hear it from the Kyoto crew. I haven’t run the tests, however. It’d be pretty easy. Just get some very mineralized but good tasting water (like Gerolsteiner without gas) and make dashi with it side by side with NY Water. Even More ballsy would be to make Stong dashi with .5 liter of gerolsteiner and .5 liter of NYC Tap and then dilute the tape with gerolsteiner and the gerolsteiner with tap (apples vs apples).

It is quite natural that multivalent cation like calcium in hard water would prevent the extraction of umami from Kombus, since Kombus are also rich in alginate.

I hadn’t thought of that.

Mr Arnold,

Kombu does not contain MSG. It contains glutamic acid to which sodium hydroxide is added to form the precipitate monosodium glutamate.

You want to use a soft water, the lower the calcium content the better.

Mushrooms contain guanyline monophosphate and katsuobushi contain inosine monophosphate. Both are 5’ribonucleotides and act in synergy with glutamic acid to enhance the umami experience.

The ideal extraction for kombu is 60-63C although this is debatable and I have tested 65C as well. For my extractions I use a water bath and glass beaker. Anything over that and you are extracting elements of chlorophyll which can be bitter and vegetal. To create the dashi you will then use a second water bath (or just remove the kombu and heat to 80 C) Add katsuobushi, allow to sink and strain through micron filter (super bag or even coffee filter). Process shouldnt take more than 2 hrs.

Hope this helps.

W.M. Batchelor III

While there is no added MSG in Konbu, and it’s true that aqueous glutamic acid mixed with NaOH once dehydrated will produce crystalline MSG; since MSG freely ionizes in water to form glutamic acid and sodium, and kombu contains both free glutamic acid and ionizable sodium (plenty, in fact), wouldn’t you agree that konbu, for all intents and purposes, contains MSG?