by Dave Arnold

Becoming a Mexican grandmother is one of my lifelong goals. I am proud to say I’ve achieved one of the major milestones: learning to nixtamalize corn and make tortillas from scratch. Along the way I’ve uncovered some cool facts and developed a eurotortilla made from nixtamalized rye. Next step: learn Spanish.

Nixtamalization is the Nahuatl word for the cooking and steeping of corn in alkaline water. The steeping liquor, known as nejayote, is drained off after the process is complete and the remaining corn is washed to remove a portion of its skin and excess alkali. At this point the batch of corn is known as nixtamal. Nixtamal can be ground to produce the dough known as masa –from which we make tortillas, tamales, tlacoyos, etc; or it can be left whole and boiled again to produce the puffed up boiled corn used in posole.

Nixtamalization was invented in ancient Mesoamerica, now Mexico and central America, over 3500 years ago. The alkalai of choice in this region is calcium hydroxide (slaked lime). Nixtamalization spread with corn culture to the American southwest, where nixtamal is known by the native American word hominy, and potassium carbonate (potash) and lye are the common bases. Nixtamalization eased the workload of women charged with performing the back-breaking labor of grinding corn. Untreated corn is extremely difficult to grind by hand –especially using the traditional Mesoamerican metate e mano:  a stone table and rolling pin. The alkaline water of nixtamalization partially dissolves the corn’s hard skin (the pericarp), allowing the grain to take up water much more quickly and grind much more easily. Besides this fundamental benefit, nixtamalization does much more:

- Nixtamalized corn has an amazing aroma and flavor, which is why a tortilla doesn’t taste like plain cornmeal.

- Nixtamalized corn makes a fantastic masa –ideal for tortillas, tamales, tlacoyos, etc. Untreated corn doesn’t — we’ll see why later.

- Mature corn, as opposed to green and sweet corn, is deficient in available niacin. It contains plenty of bound niacin (as glycosides associated with proteins) and alkali processing releases it. European invaders did not realize this crucial fact when they appropriated corn as a staple grain. Because western milling technology was so advanced, they didn’t see the need for nixtamalization. As a result, Pellagra, a horrific disease brought on by niacin deficiency, plagued and sometimes killed poorer Europeans and Euro-Americans who consumed primarily corn.

- If calcium hydroxide is used as the alkali, the calcium content of the corn skyrockets. Nixtamalized corn is the primary source of calcium for many people who consume tortillas as a staple.

- Alkali processing deactivates nasty aflatoxins – poisons due to fungal contamination. Some evidence indicates that these aflatoxins become active again in the acidity of the stomach – the research is inconclusive.

- Nixtamalization improves the protein balance in the corn by washing away some nutritionally low quality zein protein. Thus the remaining protein is higher in nutritional quality, but the total protein content is lower.

Learning Nixtamal:

Why should you learn to make nixtamal? Home-made tortillas less than an hour old are so far superior to typical store fare that they should not be known by the same name. Old tortillas are good for frying and that’s about it. Making tortillas with maseca, dried masa flour, is not a close second. Tortillas made from fresh masa taste better, and making and grinding your own lets you control the texture.

By the way, when I say tortillas, I mean corn tortillas –God’s tortillas. Flour tortillas are comparatively soulless, though they have their uses. Corn tortillas are amazing because their perfect taste and texture comes from such simple ingredients: corn, water, calcium hydroxide. No added fat, no added anything.

Let’s explore Calcium Hydroxide, the magic ingredient of nixtamal, before we look at the process itself.

Calcium Hydroxide, or Cal, the magic mineral:

Calcium Hydroxide, Ca(OH)2 or slaked lime, is a weakly soluble, alkaline chemical commonly made by burning limestone or seashells at very high temperatures to produce lime (CaO) and then “slaking†the result with water. It is one badass ingredient. In Mexico it is known Cal, Americans often call it “pickling lime,†and Thais call it lime paste. It is one of the primary alkaline cooking ingredients in the world (for Harold McGee’s interesting article on alkaline cooking in general see here. See the end of this post for some international and awesome non-nixtamal reasons to use Cal). Since cal is only weakly soluble in water, you’ll be working with slurries and not solutions. Add Cal to water and break it up to form a cloudy liquid. Most of it won’t dissolve. When you cook the corn, add Cal based on the weight of the corn, not the weight of the water.  The weight of the water isn’t as critical; the Cal is in excess of what can dissolve. As the process uses Cal, more will be dissolved into the water. Recipes vary widely, but a good value seems to be 1 percent  Cal by weight of corn (1kg corn gets 10 grams Cal). You’ll add water at about two to three times the weight of the corn (I do three, since some evaporates off and I’m making small batches).

Finding Corn:

You don’t use sweet corn for nixtamalization, you use field corn –of which there are a bazillion types. Field corn is shockingly hard to find in New York City. Popcorn can be nixtamalized, but the results are poor because the skin is especially tough and the endosperm is small and hard. I’ve done it, but I don’t recommend it. Tortilarilla Nixtamal here in NYC turned me on to their supplier: Rovey Seed. I get white (the traditional favorite) and blue (awesome) field corn in 50 pound bags, which costs more to ship than to buy.

What’s going on in Nixtamalization, and the Basic Procedure:

Good masa is cohesive (it sticks to itself) but isn’t adhesive (it doesn’t sticky to your hands.) It is also soft, moldable, and inelastic. All of these qualities are essential to making tortillas and are delivered by the nixtamalization process. When you cook and steep the corn with Cal, the alkalinity of the water starts softening and dissolving the pericarp of the corn kernels. This skin is later removed, but not entirely. The dissolved skin becomes a mass of gummy polysaccharides that act like a hydrocolloid, imparting good working qualities to the resulting masa. Nixtamal that is over-rinsed after steeping, or that is made with corn from which the pericarp has been mechanically removed, doesn’t have this workability. The cooking in Cal also gelatinizes a portion of the starch in the corn. This starch adds structure to the masa that would be absent if the cooking step were omitted.  During steeping some of the gelatinized starch retrogrades, or recrystallizes, which some authorities believe is critical to masa structure. During steeping the calcium also penetrates further into the endosperm, increasing the calcium content of the masa.  Surprisingly, though steeping times can be as long as 24 hours, the water content of the corn does not increase significantly during steeping. Cooking with Cal also brings out the characteristic fantastic aroma of tortillas and saponifies (the process by which fats are turned into soap) some of the fat in the corn germ, adding to the characteristic taste. The corn germ, which contains a good portion of the corn’s oils, also absorbs a lot of calcium and is vital to the texture of a proper masa. A study making masa from de-germed corn deemed it worthless. Other reactions taking place during nixtamalization are the polymerization of proteins and the complexing of fats and starches (see references at bottom).

Getting it Right: Â visiting Tortillerilla Nixtamal:

Nixtamalization procedures are all over the map. Cooking times vary from 15 to 90 minutes. Cooking temperatures vary from 80 C to boiling. Steeping times vary from a couple of minutes to over 24 hours. Since I didn’t grow up making Nixtamal, I needed a reference from someone who knows what they’re doing.

As much as I love New York City, I am disappointed to report that there is only one establishment in this whole place that makes its own tortillas from raw corn: Tortillarilla Nixtamal in Corona, Queens. All other shops buy tortillas or make them from maseca (masa flour). Shauna Page, one of Tortilla Nixtamal’s owners, graciously gave Nastassia and me a tour and showed us the ropes. She showed us her corn, she showed us her nixtamal, she showed us how to rinse it. She demonstrated how to get the proper texture and how to grind it. She also gave us some fantastic tortillas hot off the presses. The most important thing I learned was how properly nixtamalized corn should look and taste.

How to Do It:

Add 5 grams of Cal to 1.5 liters of water in a pot and make into a cloudy suspension with a stick blender. Add 500 grams of field corn. Bring to a boil, then turn heat down and let simmer for at least thirty minutes, stirring every few minutes. Some people say that you should never boil nixtamal, because the masa will get gummy. I haven’t found this to be true. I don’t keep it at a boil, however, because at a boil it can overcook rapidly. If your temperatures are too low the process will take longer. At about the 15 minute mark, start testing corn kernels. Pull them out of the water and see how easily the pericarp slips off the kernel. At his stage it probably won’t come off too easily. If it does, the corn might be done.  — bite into the corn and see how soft it is. At 15 minutes it will probably still be fairly hard and not have a lot of water absorption. At 30 minutes, your corn might be done (mine usually takes between 40 minutes and 1 hour). You know your corn is done when:

- the skin is partially dissolved and the rest slips off easily

- the outside is slimy

- the corn is somewhat softened but still has an unaffected core

- it tastes like masa.

- Unless all of the above are true, keep cooking.

There are dangers of overcooking:  if you completely dissolve the skin the corn will rapidly take on water, the starch will get completely gelatinized, and the corn won’t be good for masa. If that happens, let it cool, rub off the remaining skin, rinse under water, and continue to boil the corn in salted water (or use the official Mexican mineral salt: Tequesquite) till the corn puffs up into posole corn. After the corn is cooked let it steep. I have found that the steeping time isn’t critical. As long as the corn steeps a couple of hours the masa seems to work fine. Some people “quench†their nixtamal to stop the cooking process by adding some water to the pot after the heat is turned off. I only do this if I think I have almost cooked it too long or am making a big batch, otherwise I let it cool with the lid off and then cover it to steep. A timing suggestion: nixtamalize at night and then let it steep until the next evening (about 24 hours) or nixtamalize in the morning and let it steep till dinner (8-10 hours).  After steeping, drain the corn into a colander and rub your hands through it to break up some of the dissolved pericarp. Don’t worry about being rough. Rinse the nixtamal in water,  then repeat one more time. Done and ready to grind.

Grinding into Masa:

As part of my quest for Mexican grandmotherhood I needed to grind my masa on the traditional Metate e Mano.  I went north to East Harlem to find one. The metates on offer were laughably small but would have to do. The surface, I soon found out, was also way too rough — there was no way to grind effectively on it. I believe I inadvertantly purchased an ornamental metate, but I have forced it into kitchen service by grinding the surface down with a 4 ½ angle grinder and then sharpening  with a coarse abrasive block.

After hours of using the metate I can say this:

- Either there is a skill in grinding I don’t possess (possible) AND/ OR

- I am incredibly puny (probable) AND/OR

- Mexican Grandmas are some of the toughest people on earth, BECAUSE

- Grinding corn the old fashioned way for a group of 12 people is no joke.

I have not given up on the metate –I’d like  buy a full sized one in Mexico and learn from a local, but for now I am on to other techniques.

The food processor is an obvious choice, but I don’t really like it. It takes forever to grind, and requires the addition of too much water. You always need to add a little water to the corn when grinding masa, but you shouldn’t have to add a ton. The processor works but it ain’t great.

I had high hopes for our Santha Wet grinder –the Indian grinding machine we use to make chocolate (which is traditionally ground in Mexico on a metate), but it was similarly disappointing.  I made a fantastic masa by pre-grinding in the food processor and then finish grinding in the Santha, but the process was laborious and it took the Santha 35 minutes to achieve a texture I liked.

My current favorite (although I don’t like it that much) is the Victoria/Corona corn mill, made in Colombia. It makes a good masa –if you grind it twice. Don’t try to use it for anything else – it’s no good for making flour.

I add salt to the masa after the grinding process –to taste.

A note on authentic Mexican kitchen equipment: you will have the same sourcing problem I had with the metate if you’re looking for a molcajete.  These traditional stone mortar and pestles are used in Mexico for grinding spices, pounding avocados, etc. I bought mine 12 years ago and it is one of the workhorses of my kitchen. The ones the national kitchen chains (you know who you are) sell now are a joke –you could lose whole pepper grains in their surface

Forming Tortillas:

I wanted to learn the traditional hand-slapping technique for making tortillas without a press, and maybe I’ll get good at it someday. For now I am barely passable and am slow as anything, so I use a cast-iron tortilla press covered with a sheet of plastic wrap as a release agent. Don’t bother with light or flimsy presses.

Cooking:

I cook the tortillas on a dry crepe maker, griddle, flat top, or hot pan. You want hot –like 200C or more. Cook it for about 40 seconds, flip, cook about 40 seconds, flip and cook again. The tortilla should start to puff a little. If your masa is very course, it won’t puff –don’t worry about it. Sometimes I cook longer, sometimes I flip a couple of times. Do it by eye.

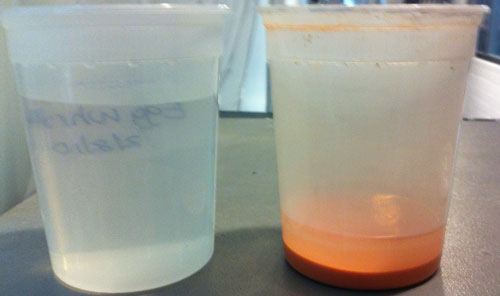

Blue Corn pH Test and the Quixtamal connection:

One day while nixtamalizing blue corn I decided to see if I could speed up the process by completely omitting the steeping step and cooking the corn for only 10 minutes in the pressure cooker at 15 psi. I would be the inventor of the revolutionary Quixtamal ™ fast nixtamalization! Not so much.  I was able to make a passable masa, but the flavor wasn’t as good as traditional and, as you can see in the picture below, the color wasn’t  right. The reason? The blue color in corn is due to anthocyanin pigments. These pigments are highly pH dependent. In Neutral and acid conditions they tend to purple and red, in basic conditions they tend to blue and green. The traditional masa is bluer because it is more alkaline and tastes more like a traditional tortilla –a visual check of the process of nixtamalization.

Non-Traditional Grains: The Rye Eurotilla.

Corn is the traditional grain for Nixtamalizing, although sorghum is also used. Sorghum and corn have similar seed coats, so it makes sense that they can be processed the same way. I wanted to try other grains –like rye. Unfortunately, Cal wasn’t a strong enough base to melt the seed coat of rye, so I switched to a stronger base –lye (NaOH). I simmered rye in a 1 percent solution (based on water weight) solution of lye for 4-5 minutes (until the pericarp started to dissolve), then drained the rye, rinsed it thoroughly and transferred it to a pot with water and cal (at 1 percent cal by weigh of rye) and continued the nixtamalization process  as I would for corn. Watch out — the small rye grains can overcook very quickly. When the grain was done I quenched the pot with water. Why use two different alkalis instead of just lye? I believe that nixtamalizing with Cal produces a different flavor than lye, and lye alone would be too easy to overdo. I just used the lye as a kick-starter and then went traditional. The resulting tortillas were amazing. They had traditional tortilla aroma, minus corn, plus rye. The masa was a bit sticky (probably due to rye pentosans), but released well from the plastic wrap and the cooked texture was fantastic. I am extremely proud of the rye tortilla –nothing but the rye, cal water, and salt! I have tried nixtamalizing partially milled faro with Cal, no lye. It worked, but is very finicky because so much of the pericarp has already been removed – it’s very easy to overcook.

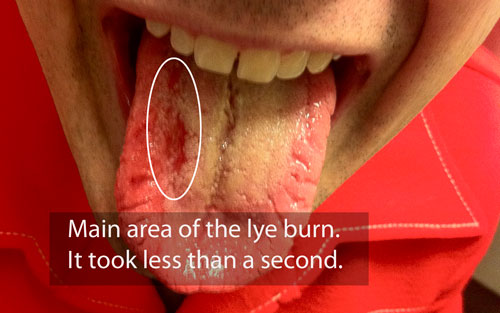

A Note on Lye:

Lye is dangerous. Really. I have dozens and dozens of quart containers filled with various powders –none of them dangerous to taste except lye, which I use very rarely and expect to be labeled. Last week someone brought me an unmarked quart container and asked what it was. Stupidly, without thinking or looking I put my finger in the powder and put it on my tongue. It felt like my tongue was on fire –like I ate 50 Szechuan buttons at once. Strangely, it didn’t taste basic or slippery. The only tastes I could discern were salt and what tasted like acid (I don’t know why). Thank god I didn’t swallow. I instantly spat out and flushed my mouth with water for 10 minutes before going to the emergency room. My tongue and the roof of my mouth were bleeding. The taste buds were burnt off half my tongue. Luckily, the tongue heals fast, although I’m still not 100 percent. The first thing I did when I got home from the ER was get rid of any lye in my house. The thought of my kids getting anywhere near that stuff makes me sick. Use caution.

Tortilla de Pollo, A Recipe from Fabulous’ Abeuela.

Last, but not least, our Mexican former intern Fabulous, fresh off a stage at Noma, told me that his grandma nixtamalized with chicken stock instead of water, so we tried it. It was fantastic. Maybe the best tortillas yet. The corn has to cook longer in the chicken stock –45 minutes to an hour at least. I don’t know why, but the skin doesn’t dissolve as quickly. Perhaps the chicken stock uses some of the cal and the process could be speeded by adding more.

The Tantalizing Aroma of Tortillas

I asked Harold McGee about tortillas’ characteristic aroma, which he said is mainly due to the compound 2-aminoacetophenone. He said the same compound gives chestnut honey its distinctive odor. I bought a container of chestnut honey and dag nab if it didn’t smell of tortilla. He sent me some papers which claim 2-aminoacetophenone is a breakdown product of tryptophan –an amino acid in the tortilla (see references at the bottom). But corn is famously deficient in tryptophan and lysine — why would the aroma of tortilla depend on something in which it’s deficient? This nagging question lead me to believe it was, perhaps, niacin breakdown products that created the aroma. Niacian and tryptophan share some similarities and are part of the same metabolic pathways … and Niacin is released in nixtamalization. I boiled some niacin supplements with Cal and could detect no difference compared with plain water and cal. Guess it’s not the niacin. I am still stumped.

Other tortilla aroma compounds include beta-ionone (warm,fruity,woody) and methy-butanal (cocoa,coffee,nutty). Side note: the best free site I have found for investigating aroma compounds is: The Good Scents Company –you won’t be disappointed.

Special Bonus

Some More Uses for Cal –The Magic Mineral:

- In Thailand, lime paste — or more commonly a red version called red lime paste — is added to water and mixed to create a slurry. After the slurry settles out, the clear water that remains is saturated with calcium hydroxide and tastes a bit like cement (which makes sense — Ca(OH)2 is formed when cement is mixed with water). The lime water is then decanted off the paste, which can be used again. Fruits like bananas are soaked in the lime water prior to cooking. The calcium in the water cross-links the pectin in the fruit, making it stay firm even when cooked. Bananas are especially good for this trick because they are often fragile and already have a cement taste as a base note (ever tasted an under-ripe banana?). For years I have been vacuum injecting lime water into bananas before cooking – I can cook the bananas and beat the hell out of them in the pan without breaking them, and they stay firm. (If you try this trick: don’t let the calcium stay in too long before you cook and don’t use too much — you’ll taste the lime water. Very ripe bananas work best because they are super sweet.)

- Thais also add the lime water to batter for fritters. Supposedly, the lime water makes the fritters crispier, although in side by side tests with wheat based and rice based batters we have not noticed this improvement. Surprisingly, the lime water  didn’t make the batters brown faster, which I expected — alkaline conditions speed Maillard recations. What the lime water does do in a batter, however, is provide a characteristic alkaline taste (foods like pretzels and yellow alkaline noodles derive some of their unique flavor from alkaline processing) that we like.

- Slaked lime can be used to increase crispiness in pickles by the same pectin cross-linking described above.

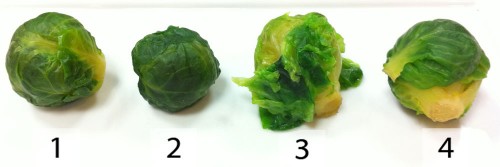

- I love this one: It can be used to keep boiled green vegetables bright without losing firmness. Every cook knows that adding a pinch of baking soda to cooking water helps green vegetables stay green. Cooking in neutral or acidic water at high heat encourages chlorophyll to lose magnesium. Once the magnesium ion is lost the chlorophyll, now in its degraded form known as pheophytin, takes on a drab color. Cooking in alkaline water (like with baking soda) prevents the chlorophyll from losing magnesium, so the color stays bright. Unfortunately, alkaline conditions also cause pectin structures to break down rapidly –so baking soda causes irremediable mushiness — which is why I don’t use it. Use calcium hydroxide instead — Its basic nature ensures vegetables stay green. Its calcium cross-links pectin ensuring that the vegetables don’t go mushy.

Selected References:

Ron G. Buttery, Louisa C. Ling (1995) Volatile Flavor Components of Corn Tortillas and Related Products. J. Agric. Food Chem., 43 (7), pp 1878–1882

Méndez-Albores, J., Villa, G., Del Rio-GarcÃa, J. and MartÃnez, E. (2004), Aflatoxin-detoxification achieved with Mexican traditional nixtamalization process (MTNP) is reversible. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 84: 1611–1614.

MartÃnez-Bustos, F., MartÃnez-Flores, H., SanmartÃn-MartÃnez, E., Sánchez-Sinencio, F., Chang, Y., Barrera-Arellano, D. and Rios, E. (2001), Effect of the components of maize on the quality of masa and tortillas during the traditional nixtamalisation process. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 81: 1455–1462.

Jesse F. Gregory III, (1998) Nutritional Properties and Significance of Vitamin Glycosides. Anuual Review of Nutrition, Vol 18: 277-296

M.G. Ruiz-Gutiérrez, A. Quintero-Ramos, C.O. Meléndez-Pizarro, D. Lardizábal-Gutiérrez, J. Barnard, R. Márquez-Melendez and R. Talamás-Abbud (2010) Changes in mass transfer, thermal and physicochemical properties during nixtamalization of corn with and without agitation at different temperatures. Journal of Food Engineering, Volume 98, Issue 1, May 2010, Pages 76-83

And I’m now ordering some corn. Arnold for President.

You. Are my hero.

Hi Dave,

once again a superb post and one I´ll try to replicate at home! I´ll steal some dried corn from a farmer who feeds his pigs with it in the neighborhood. LOL

The rye part is intriguing as well.

Some granola grinding friends of mine have a mill for their Kitchenaid. This might be the right tool for you as well.

Look up KitchenAid-KGM-Stand-Mixer-Grain-Mill-Attachment to find it.

TTFN

Hannes

Howdy Schinderhannes,

I have one of the Kitchenaid attachments. It specifically recommends not doing any wet or oily grinding. That said, since when do I heed instructions? My memory of using it is that it jams up fairly easily.

How about the meat grinder attachment? (Or a standalone meatgrinder, if you’ve got one.) I have made grainy but cohesive sunflower butter with my KA meat grinder attachment, although I did have to grind it twice.

Dunno. Maybe it would work for preliminary grinding.

This was a fantastic post! Only, I just encountered another NYC establishment that does this too, Hot Bread Kitchen in Harlem. Check it out and thanks again for this great post.

Best,

Adam

Hey Adam,

Thanks a lot for info on Hot Bread Kitchen, I hadn’t heard of it but it looks awesome. How is the book going?

It’s going well, thanks! I turn it in April 15th.

Wow. That part about pectin and green vegetables is the most amazing thing I’ve read in a long time. The rule of thumb has always been that alkaline environments lead to mushy green vegetables, but here you have found a way around that. I’m excited to get some calcium hydroxide and do some experimenting. 🙂

Howdy Charles,

Let me know how you fare.

Another awesomely informative post. I’ve always wondered why there was a boiling w/ limewater step in every Vietnamese recipe for candied fruits.

There are also recipes for (milled) glutinous rice cakes that’s been boiled in lye water – banh tro in Vietnamese, Jianshui zong in Chinese cuisine. Wonder what the lye water does to the milled rice.

Dunno,

I’ll see if I can figure it out.

In your process for achieving that desired Mexican grandmotherhood, you are more than welcome to spend some time in Mexico City with us.

We own a culinary institute and have access to traditional real-size equipment and excellent mexican chefs.

Superb post about this wonderful process.

Hello,

I might take you up on your offer!

I was absolutely serious about it.

We would be thrilled to have you here.

I’m hoping to plan a trip to Mexico sometime this year. I will definitely write you when I know when.

Great post!

The wall-to-wall carpet in my fifth-grade classroom always smelled uniformly like fresh tortilla — I wonder if some similar compound was responsible.

Hmmm. Dunno.

I love fellow obsessives! I loved this blog entry! I hunted and found an electronic grinder called Nixtamatic. It was expensive and expensive to ship but it does a fair job. The Indian grinder was a joke and the hand crank is too butch for me!

I ended up as an intern at a tortilleria in Actopan, Hidalgo and in the end I concluded it’s really, really hard work! But delicious.

The one thing I’ll have to disagree on is your advice on the molcajete. The rough surface rips and tears at chiles, tomatoes and tomatillos in a glorious way that a smooth surface, or a blender or food processor, can’t touch. For peppercorns and spices I’d use a clay bowl with texture on the bottom. I can’t remember what they’re called at the moment (chilmora? No….) but there’s room for many types of mortars and pestles in my kitchen.

Congrats on such a good read!

Hello Steve,

I saw your grinder video. I want one! I can’t seem to locate one in US.

I found it in a hardware store in Puebla!

Nice

Hi! I agree with you on the texture of molcajete. You are supposed to “cure” it first by grinding raw rice in it. At least that’s what my mom does. The clay ones with texture at the bottom are chilmoleras, great for making salsa, and is perfect at the table as the serving vessel.

This is a great post. We learn so much from you. Regarding the difficulty of grinding corn on a metate, the food historian Rachel Laudan estimates that it takes half an hour to grind enough corn for one day’s supply of tortillas for one person. (http://bit.ly/g5w2Kp) Think of the hard work of feeding a large family this way!

I just read her post. Pretty cool.

I am a graduate student studying flavor chemistry, and in my spare time I’ve collected all the flavor compounds we have in the building (some 5-600) and put them in 1% solutions for easy-smelling. I must say my ears (nose? eyes? some sense anyway) perked up at the mention of flavor compounds, and remembering I have 2-aminoacetophenone in my ketones tray, I smelled it first hand. Sure enough, it is reminiscent of corn tortillas. I will also submit that more compounds could enhance this flavor, specifically 2-acetylthiazole and 2-acetylpyridine, both of which have a very similar (to each other) roasted corn smell, the thiazole especially (think tortilla chips).

I also wanted to mention, having used The Good Scents Company’s website for the past year and a half, that, while it surely is a valuable resource (along with Acree’s Flavornet and Leffingwell’s various blurbs and threshold tables), one should take some of their odor descriptions with a grain of salt. Often odor perception is quite different at varying concentrations, and often reports will use many adjectives to attempt to describe something otherwise relatively simple. A good case in point is beta-ionone, which I suppose would have a fruity, floral aroma if you beat around the bush about it, but far more importantly, it is distinctly the smell of fresh raspberries (it’s also known as ‘raspberry ketone’). Appropriately, alpha-ionone seems to be the main basis of blue raspberry flavor.

In your post some weeks ago about eclectic collections of pears, you mentioned stopping by Corvallis, OR to visit the US National Clonal Germplasm Repository; you might also consider stopping by Oregon State University (also in Corvallis!), as I’m sure I (and maybe some fellow food science students) would love to have you. Every visitor I treat is subject to the grand tour, including at least an hour of me finding vials and saying ‘here, now smell this!’

Howdy Pete,

I will definitely make the trip to the University. I hope to come through with McGee during pear season. I wish I could come for bramble-fruits but I don’t think I can make it.

Hi Pete!

Nice to see another flavor chemist reading this blog. I’m doing a PhD at UC Davis; in our lab we do a lot of wine work but fruits, herbs, perception and psychophysics too. What do you work on?

Speaking of beta-ionone, I was making a solution of it and beta-damascenone both at 4 ppb in 12% ethanol and it smelled just like chambord. At 1% ionone reminds me of violet perfume or blackberry. You are spot-on with the concentration dependence of odor quality. Ethyl Hexanoate is another example, which smells appley at lower concentrations and kind of like cheese at higher concentrations.

Hi Arielle,

I still have a lot of the reading you gave me left to do. Hope to speak with you soon.

Hi Dave-

If you get this before my email, I’ll be in town next week and I expect you to be ready for the quiz. In all seriousness, I’m really looking forward to the MOFAD event. And can bring more reading material too if you want.

Hope you had a good time!

I had an AWESOME time. I can’t wait for the next one; I just got a fellowship so I can actually afford to come.

I’ll see you at the ECC next month!

Hi Arielle, I specifically work on sulfur aromas in wine, doing things with method optimization using the GC. At least, that’s my ‘official’ project, but I sort of started investigating all the flavor compounds as a side project, because they’re essentially the coolest thing ever. It’s really the reason I went into flavor chemistry (I was also heavily inspired by none other than Dave Arnold, after seeing him at the 2008 ACS meeting in Philly; the gymnemic acid on a Tastykake and habanero vodka sold me on what to do with my BS in chemistry; thanks Dave!).

I actually am running almost everything I have at a 1% solution, which in the flavor world is pretty high. Some super strong stuff like sulfur compounds I will have at much lower (methanethiol, for instance, will fill a room with a distinct fart smell if opened for more than a few seconds at more than, like, 1%). I have read that beta-ionone (and the other ionones in general) have a violet aroma, but I, having really no good recollection of what a violet smells like, always perceive straight up raspberry. Not imitation or jam or anything, but just the most important note of a fresh raspberry. I’ve also recently realized there is a raspberry ketone (which I, deductively, always assumed was beta-ionone), which is more scientifically known as p-hydroxybenzyl acetone (or 4-(p-hydroxyphenyl)-2-butanone). I have smelled this as well, but it smells far more like imitation raspberry and certain “Raspberry Ice” drink powders.

Forgive my digressions; I could talk flavor compounds for hours.

Also, since you mentioned it, fun fact about hexanoate (really about hexanoic acid): the hexyl group seems to carry a certain animalic quality to it. This is most evident in hexanoic acid, which is also called ‘caproic’ acid, “caproic” coming from the latin word for ‘goat.’ If you’ve ever pet a goat, or smelled one up close, you might notice they secrete the chemical from their skin. GOAT ACID.

And I guess isoamyl acetate (banana) is also a bee alert pheramone?

Yeah I saw you were doing everything at 1% and I was like, wow, brave guy. I’m going to get technical for a second so sorry, everyone else. I am curious: What’s your matrix? I would usually smell stuff in water (or, more typically, 12% EtOH model wine) but for storage you could get some pretty heavy losses from everything being up in the headspace. And I hear you on the low-threshold compounds…opening the fridge where our 2-isobutyl-3-methoxypyrazine lives is like taking a bath in liquid bell pepper. And I think short-chain fatty acids and their derivatives are kind of a skanky group, generally. Butyric acid, for example.

I was a GC-O panelist for some wine sulfur stuff last year. Have to say I don’t miss it. I’m doing mostly norisoprenoids myself now, and I empathize with you in your method development. For sulfur are you using a chemoluminescence detector? I am mostly single and triple quad MS myself.

beta-ionone kind of reminds me of creme de violette mixed with blackberry jam, a little more perfumey than a raspberry smell. I’m kind of on a sesquiterpenoid kick lately, though. Zingiberene or rotundone, anyone?

I don’t know if you can PM me or anything on this but I’d love to keep in touch about flavor… I am ajohnson ((at)) ucdavis ((dot)) edu

I enjoy reading about your work with pressure cookers, especially when you point out when things DON’T work out and why!

Thank you!

L

Most of the humus (chickpeas) places use weak alkaline water (baking soda) to soften the outer skin and shorten the cooking times, even if they don’t openly admit it.

Trying out different levels of alkalinity with different ingredients using Calcium Hydroxide is definitely a thing I am going to try.

I am extremely curious about the possibilities of nixtamalized indigenous grains, even small ones like the Ethiopian Teff. I think the flavor results can be interesting.

Thanks for a great article.

Please keep us posted.

Incredible in depth research and report! Am posting on Facebook immediately…. and yes do come and visit Mexico City ( so many culinary schools) and we’ll help you find a molecajete and a chilmolera ( clay grinding bowl).

http://www.mexicosoulandessence.com

Thanks!

You might wnat to take a look at http://www.culianriamexicana.com for the news on all things food in Mexico – with a bilingual column called Mexican Ways.

Fascinating topic–thanks for exploring. Calls to mind a recipe given in Diana Kennedy’s Nothing Fancy cookbook for preserved peaches using (good, clean) wood ash. Cal definitely easier to come by and so may finally give this one a try.

Thanks for yet another great post!

If you have some calcium hydroxide left over, why not try a DIY mineral water? Latest version of the calculator can be downloaded from: http://bit.ly/eFp0C7. For more information, see http://blog.khymos.org/2011/01/30/diy-mineral-water/

Hey Martin,

That calculator is pretty cool. I like it a lot. I have all the salts (I played with fake mineral water a bit after reading fix the pumps). I didn’t spend enough time to get good. Have you done any side by sides to see if the manufactured waters resemble the originals? I see you have my favorite highly mineralized water –Apollinaris, and my second –Gerolsteiner.

This is a great article. Hope the burn heals for you. That is terrifying. And come out to Chicago sometime–ridiculous amounts of fresh masa available, and I’m guessing you could find some solid equipment at Maxwell Street Market.

Thanks for such a great piece.

-Hugh

Just looked up Maxwell Street Market. Definitely on my list for my next Chicago trip.

Brilliant!

You must be more careful with chemicals though. We do not want to lose you.

I read somewhere that browning meat with baking soda intensifies flavor. Did not try it myself and could not find a reference on this site. Perhaps a project for your interns?

Thanks Jurgen,

A number of years ago some cooks (I think in Belgium), started adding baking soda to meat to intensify and speed maillard reactions. I first heard about it from McGee. We used to do the demo in the class we teach together. I must say I never really liked the results that much –although maybe we used too much. I have been able to get some interesting results sauteing onions with baking soda, but I only ever did it experimentally. The guys over at Modernist Cuisine put some onto veggies in the Pressure cooker to work maillard magic –but I haven’t played with that.

Hi Dave,

What a joy to read this from — who knew — a fellow nixtamal nut. Two suggestions below.

The Ultra-Pride wet/dry grinder shown here is excellent at grinding the nixtamal:

http://egullet.org/p1704315

It’s hard to find them in the US but you probably could track one down. I think that the granite rollers have more give than the Santha, which allows those big kernels to get underneath.

In addition, Diana Kennedy suggests using a thick (freezer) Ziploc gallon bag that has had the zipper and two sides removed, leaving only the bottom edge. It fits that Victoria press perfectly and is much easier to negotiate than thin plastic wrap.

Great job finding a source in NYC; until I read that, I had been told, repeatedly, than none existed in the northeast. So I’ve had to smuggle my corn from Tucson using the family as mules:

http://egullet.org/p1766332

Cheers,

Chris

Thanks Chris,

I’ll check out the Ultra Pride. I am now salivating over Steve Sando’s Nixtamatic, which appears to be unavailable in the US. So much for finding anything over the internet. I’ll definitely try the Zip lock next time.

Hi Arnold!

I would love to see a post on sushi rice; comparing types of rice, washing techniques, water amount, vinegars etc. Feel that this area of gastronomy is rarely scientifically explored (at least not in the western cooking world), but still there are so many variables to have fun with!

Sincerely yours

Lowe

Hello Lowe,

Rice in general is a fascinating subject.

Hi Dave,

That lye burn looks ridiculous. I hate to say it but i am glad to see this post because there have been times ive done the same thing(Someone hands me a mystery hydrocolloid container and I taste it) but i will never do that again. Mexican food is so good hopefully people will get into real mexican food more. My wife is Dominican check into Dominican food, also delicious. Sancocho a very labor intensive stew is one of the best ever. Learn Spanish its relatively easy and very rewarding.

I know, I really should learn Spanish…. and make some Sancocho.

What a fascinating and informative piece. But it was so difficult to read past the picture with the can of pulque. Where in the US did you find that?

BTW I did read to the end of the piece quite happily, if thirstily.

Howdy Matthew,

I got that can in a Mexican grocery in Spanish Harlem. I’ve never had the real deal, but a Mexican friend said it didn’t taste quite right …so you aren’t missing out.

How much calcium hydroxide does one need to add to water for keeping green vegetables firm? I don’t want to overdo it.

Howdy Chas,

Unfortunately, I didn’t measure. Doesn’t take much.

Great article. Very interesting indeed.

Have you seen the work Andoni Aduriz has been doing with Calcium Hydroxide and vegetables at Mugaritz?

No, but I have heard about it. I assume he is using the firming properties?

Daaang.

OK Jay, I checked out your about me page…. How do you open a beer bottle with your teeth?

Wow! Thanks for such a wonderful, well-researched post. I’m studying Mexican gastronomy right now in Mexico City and we made tortillas from scratch during the first month of class — it took me 2 1/2 hours to season my metate, and another 2 1/2 hours to grind one kilo of corn. My conclusion is that Mexican grandmothers are stronger than me. By the way, if you’d like to know the Nahuatl name for the mano, it’s “metlapil.” Our teacher insists we use that name instead of mano in the class.

Also, I wholeheartedly second the Nixtamatic. I bought one at Casa Boker in Mexico City last year, and it was pretty much a life-changer. (It was Steve’s video that made up my mind.)

Thanks again for delving so deeply into this fascinating process!

Thanks Lesley,

How much was the Nixtamatic? I hear it is between 200-400 US.

Yep, it’s about $310 USD. I spoke with the Nixtamatic folks today, coincidentally — they’ll ship to the U.S. about the same price.

310 Shipped? do you have a contact?

Absolutely fascinating!

Though I disagree with your assessment of flour tortillas as being “souless”. A fresh flour tortilla, full of delicious lard, is wonderful and an integral part of Tejano food culture.

A friend of mine texted me the same sentiment. He said I don’t like flour tortillas because I’ve only had crappy ones… which is fair.

Yeah, I mean, properly done, I think flour tortillas can be just as reasonable a flatbread as all of the other flour contenders.

Thanks for this post. You have no idea how many times I’ve searched the web trying to find exactly what you’ve covered here. Funny to finally have it written here, one of my bookmarked blogs I check from time to time.

Concerning the grinding, I’ve wondered about using a finely ground, whole-grain corn meal. Any thoughts on that? I eventually decided as I was not at actual risk for pellagra I didn’t have to worry about the nixtamalization step. But is nixtamalization what separates masa from polenta? (It seemed that way, but no one ever drew the connection between the two — everyone always wrote exclusively of one or the other — so I was never able to be sure.)

BTW,do you take requests/topic suggestions? Not that I have any at the moment, this post was it! 🙂

BTW2, I’ve been a reader for over a year now and absolutely love all your articles and the thoroughness of your science. Again thanks for sharing such excellent work.

Thanks for the kind words AllanF,

MgGee did some experimenting with nixtamalizing whole grain cornmeal. If my memory serves, he didn’t have much luck.

We don’t take requests per-se, but I’ve had fun exploring some of the questions that I’ve been asked for the radio show.

Hi Dave, just a bit on tortillas and masa…. in Guatemala and further south , tortillas are shaped differently than the tortillas found in northern Mexico, tortillas are usually shaped by hand and cooked in a flat oval cast iron skillet, ranging from .50 to 1.20 mts., depending on the establishment, being shaped by hand means that tortillas are 1/5 of an inch in average and are cooked about 30 sec. by side, leaving a crusty outside and soft delicious inside, this is further enchased in el Salvador by making them a bit fatter to incorporate delicious fillings, most prominent cheese and chicharrones (pork rind), you can find almost the same approach deeper south in Venezuela and Colombia that are arepas, and are crafted differently with corn meal. I have played with different colors of masa with “modern†flavors, very neat Nuevo Latino cooking.

Here are some names for different tortillas

Tortillas: masa tortillas

Pishtones: fatter tortillas

Tayuyos: have black bean paste or whole black beans incorporated in to the masa

Cheers!!!!

Thanks. I’ll be sure to try regional differences. I hope to go to Panama and Columbia later this year. I hope to go to Mexico first, but we’ll see.

This is so cool and fun to read about! Thank you especially for the link to that NY Times article, it gives a seemingly good replacement for Kansui if I can’t find any here in Chinatown to make noodles for tonkotsu ramen 🙂 And egg noodles without eggs:)

have you ever tried to nixtamalize amaranth?

thanks for your research!

Hello,

I haven’t, but I’d be willing. Probably difficult to time because the grains are so small.

So pleased to finally read a breakdown, with the science, of nixtamalization!

About the steeping in chicken stock… was it salted? I suspect that may have altered the absorption, as well as the fat content.

I have a Champion Juicer that makes perfect nut butters. I plan to try it for grinding.

Thanks!

Hi Shelley,

Our chicken stock doesn’t have added salt –but of course contains salt.

Shelley,

Did you try the Champion Juicer to grind teh masa? Did it work?

So, I know you say that popping corn is suboptimal for nixtamalizing, but in your opinion, would fresh tortillas from popcorn be a step above, or below, ones made from Masa Harina?

I ask because I already have on hand: a grain mill, about 20 lbs of popping corn, and a tortilla press, and can easily obtain a small amount of Calcium Hydroxide.

Hey Walter,

I think the taste will be OK (it was for me), but the texture will be difficult to achieve because the popcorn kernels are tougher. Make sure your grain mill can wet-mill corn. You should definitely try the process, even if your corn isn’t ideal.

I have a tomato soup that I cook basil & scallions in. If I had calcium hydroxide to it, will it keep those greens green, without screwing the sharpness of the soup?

I don’t think so PHF. The soup would need to be basic (instead of acidic) to get the effect. I think you’d be screwed. Interesting problem though.

THANK YOU THANK YOU THANK YOU for this excellent blog! I have been living in Tanzania for 2 years now, where one cannot find corn chips at all, but is surrounded by corn which the Tanzanians grind (without nixtamalizing) into a flour that is used to make the ubiquitious “ugali” basically a corn gruel that is eaten and loved nationwide. Every time I read that Mexicans cook their corn with lime, I thought it meant the citrus fruit, and couldn’t figure out why my attempts at making tortillas never worked – always porridgy. I had tried evertying, even popping popcorn and processing that into a dough.. cooking it, just made a greasy cracker. So, now the mystery is solved! Now my only problem is: where will I find calcium hydroxide? Not an item sold here at all. I might be able to find some kind of scaled lime in a hardware store, can I use that? Is there anything else that can be used to substitute and get the same effect?

Happy to help Ruth! Calcium Hydroxide (slaked lime) can be got under the name pickling lime. I don’t know if betel nuts are chewed as far south as Tanzania, but Calcium Hydroxide is used with that. Builder’s lime is Calcium Hydroxide, but I don’t know how pure it is, or what its impurities are. Potassium Carbonate (pearlash or potash) can also be used. While lye is possible, I’d steer clear. It might be possible to heat baking soda to produce sodium carbonate (which is easy) and use it for nixtamalization –but I haven’t tried it so I can’t vouch. Let me know what happens.

Great post (is it offensive to just call it a post?) as always Dave.

I tried applying the banana technique you talked about to rhubarb because its just one of those annoying things to cook that has such a low margin of error between being raw and mush. I don’t have a vacuum sealer so I just soaked it for 30min and I was impatient and only had frozen rhubarb so I just soaked it from frozen. The result I ended up with was that the cut ends and skin were cohesive after cooking compared to the unsoaked sample I did. I think it would need longer soaking times or do be forced in under vacuum to really work well. The downside was that the pH made the pigment in the rhubarb turn blue (only the ends but that would be because of the low soaking time) and maybe you need the rhubarb to turn to mush to get the sweetness into it. I was actually surprised it had the effect it did because my experience with rhubarb while making jam is that it doesn’t have very much pectin in it.

Oh also after soaking the rhubarb in CaOH I soaked them in tap water for a bit so that the flavour wasn’t effected. Do you do this with bananas or is it fine just to leave it how it is?

Hi Andrew,

I leave the bananas as is, but perhaps a rinse wouldn’t be a bad idea. For years I made the recipe and was always happy. Recently, I have had a couple of batches that tasted chalky –too much CaOH I think. Blue Rhubarb!

Ok, so this may be a stupid question, but would a vitamix work with the dry blade for grinding?

Hello Stori,

Unfortunately not. The vita-prep will clog up no matter what blade you use.

Hey Dave, great post, as always.

Im a Colombian currently living and working in Mexico, so my relationship to corn is pretty deep.

It was exciting for me seeing that you used the Corona corn mill made in Colombia, it’s the mill we use to grind corn to make arepas and empanadas, however theres no nixtamal involved. I wonder if you have any information about why do we grind our corn without nixtamal, and we end up with a perfect masa for the job (cohesive, moldeable, unelastic), obviously without the delicious taste and aroma of tortillas. It may be because of the type of corn we use or the stage of the grain in which it’s harvested? Im gonna ask my mom for a precise recipe for basic masa for arepa and re post it.

Also, you posted that the corn mill shouldn’t be used to grind anything else, that’s not true. In Colombia we also use it to grind yuca (cassava, mandioca), to make masa for “carimañolas” which are kind of empadanas filled with cheese or meat, but made with masa of cassava and deep fried, crispy outside and soft and sticky inside. This is a common dish from the atlantic coast of Colombia. (If you’re interested I can also send you this recipe). By the way it’s Colombia, not Columbia. 😉

Also when you go to colombia, make sure to go to a restaurant called “Doña Elvira”, thats the real food from Bogota and the region.

Sorry about the mis-spelling Giuseppe! I will fix it right away. What I meant about grinding nothing else was it doesn’t do a good job on things like wheat flour. I should have been more specific. I would love to try Colombian masa sans nixtamalization. I hope to go there later this year. I’m not sure if I’m going to Bogota or Cartagena

You will now try sans nixtamalization masa and carimañolas here in Bogota, ill make sure. Great wine and food festival.

You bet Giuseppe, see you there.

Great article!!!

Even though Mexican food is very popular around the world one rarely finds fresh corn tortillas.

I have came to the conclusion that the lack of a moderately priced nixtamal grinder, that fulfills American and EU safety standards ( Nixtamatic grinder does not) is the reason why one does not find fresh corn tortillas around the world.

The true challenge of making good corn tortillas outside of Mexico is the grinding process. Using your local corn type, through experimentation and time it is possible to make a tortilla that is much better than store bought or those made from a processed, dried nixtamal mix.

Grinding on the other hand is not so easy to accomplish. The grinding process is extremely important. The grind must be very, very fine. If you regrind your nixtamal in an attempt to get a very fine grind, the dough easily become gummy. This is not good.

I would like to compare notes on other peoples grinding knowledge and experience. Maybe someone has found a machine that actually works at home or maybe we can come up with the best solution. Ideally, I would like to have an electric machine that would perform the job. Preferably the size of a household electric meat grinder that is easy to cleaned. I need to be able to make tortillas regularly without hours of manual grinding or extensive clean up (dishwasher safe components would be best, just like my meat grinder). Aluminum is not good since it will react with the slaked lime.

Her is my experience:

Nixtamatic grinder (electric): Though it is specifically made for grinding nixtamal, my impression is that is does not grind as fine as it should, it is very expensive and workmanship quality is not good. At first it works well, but the grind deteriorates quickly. I have not tried it myself but have spoken to some that have used the machine. Has aluminum parts.

Wonder mill Jr( manual): The auger is too small and the cone shaped body also too small. It will not pass the wet corn.

Wonder Mill impact grinder (electric): Wonderful machine but the corn must be wet when grind to achieve the proper geletization. This machine only grinds dry.

Grainmaker from Montana (manual, electric and pedal): Very, very good result but for everyday use it is too much work to grind by hand. I have not tried to set is up with the electric motor. Very expensive but very, very good quality. This is the best I have found thus far. The grinding quality is like that you will find in Mexico. It is too big to have in the average sized kitchen. Rust since it is designed to grind dry. Care must be taken to avoid this. Much work to clean up. One of the grinding plates is not easily removed and therefor difficult to clean.

Country Mill: The design of the grinding plates slightly into the body of the grinder causes the dough to get stuck and result in more torch needed to turn the handle.

In addition: Metates are to much work, meat grinders do not grind fine enough and ordinary kitchen machines require too much water to grind. Authentic Mexican electric grinders are too large and dangerous for household use. The stones must be redress regularly. That is a skill that takes years to learn.

All in all I have tried about 10 different mill both stone and burr mills. I do not remember the names of them all, just now

I have considered having my meat grinder redesigned. Does anyone know someone that works metal and/or an engineer that can help redesign.

Hope to hear from you soon!!

That Grainmaker does look nice. I couldn’t find any references to it used as a wet grinder, you should tell them it works for that application so they can put that on their site. My wife would decapitate me if I spent that money on something that would take up even more space in my kitchen.

I posted a query over the radio forum and had meant to call the show (but being in the UK has made it tough and I have lost the email address I sent an earlier question to!).

I’m wondering whether I need to use intact kernels or can you use broken (cracked) kernels? (most field corn here is sold as bird feed, a lot of it as cracked kernel). It’s a shame that it’s so hard to get field corn everywhere since I really want to try this out.

Hello JB,

The problem with cracked corn is the rapid absorption you get through the exposed endosperm. Usually, when I am nixtamalizing, the cracked kernels get very badly overcooked. If they were all cracked you might be able to work around it. Another option might be to use a stronger base which would melt the pericarp before the cracked kernels overcooked.

I cannot thank you enough for this post. Really explains the process well although I envy your little stage at the tortilleria in New York.

I imported hominy and pickling lime from Anson Mills at vast expense (I’m in the UK, yes this englishwoman is also trying to become a Mexican grandmother).

I had one attempt (I only have two 500g bags of Hominy) which is detailed here: http://marmitelover.blogspot.com/2011/05/supper-club-conference.html half-way down the post.

It was a failure.

I have one more bag and I will have another go. Your post has made success a little more likely.

Re pestle and mortars…in the UK we can get fairly cheap Chinese stone ones. But the one I have is small.

On the Anson Mills website they don’t really go into the grinding bit in any detail: you get the feeling it’s easy.

From your post I know better.

I do have a thrift store meat grinder that looks like the machine you have, so I’ll try with that.

Thanks again

msmarmite

x

Hello MsMarmiteLover (are you a lover of the pot, the yeast spread, the stock we refer to as Marmite, or all three?),

Those guys at Anson Mills certainly do know how to charge money.

Just going back through all the comments.

Ruth: I believe Indian shops sell culinary lime and there are plenty of Asian shops in Tanzania.

I also tried making cucumber dill pickles with the pickling lime, they were delicious and worked well, however you must rinse the pickling lime off well, like 3 times, as after a couple of weeks the flavour starts to emerge from the lime and they taste a bit chemica.

Andrew: Rhubarb, my favourite way of cooking it to retain crispness is to merely cover it with water and some sugar, while it’s laid in a baking tin. Put in a low oven for ten/ fifteen minutes. It doesn’t turn to mush.

For Uk residents: regarding the tortilla press, you can get one at the coolchillecompany but I found exactly the same thing but much cheaper at Indian shops (again) in Wembley. The press is used for chapattis and is called a chapatti press.

For rolling out chapattis or tortillas by hand I find a very slim chapatti rolling pin, rather than a standard sized rolling pin, does the job…much finer.

Another thing: for making pretzels , for that water bath before baking, I found adding copious loads of baking powder gave a similar shine/texture to authentic pretzels …but I wonder if a sprinkle of pickling lime would do the trick. Too scared to use Lye.

Do mean soda, or powder? Powder shouldn’t work right. Shiny yes (bagel like) but not dark brown.

Hey guys,

Just thought I’d let everybody know that Tortillarilla Nixtamal has just opened a kiosk next to City Hill in Lower Manhattan. It’s just East of CH in the plaza S of the Municipal Building

I read this blog whenever I can, and had just recently read this post when, last week, I saw a guy at a S&*(buck’s by City Hall decked out head to toe in Tortillarilla Nixtamal gear — bright yellow T-shirt, hat, etc. I told him I had read about the place on your blog, and he told me about their new stand, which will be open 9-10 months a year.

Had some tacos and tamales there last week, and noticed they also sell tortillas by the pound, not hot off the press but best one can get without a trek to Queens, I guess. Also: Mexican Coca-Cola.

Anyway, thanks for the great post!

Thanks for the info Destruction

Dave, I mean baking soda of course!

Exhausted after all my nixtamalisation attempts…

I meant the yeasty substance!

Here’s my post on how to make it…but…I have a problem with bitterness…any suggestions?

http://marmitelover.blogspot.com/2011/04/how-to-make-your-own-marmite.html

This article rules, I love tortillas. I’ve been looking for hominy in the northwest with no luck, so now I’m excited to make my own too!

I have experience using lime paste in the Thai restaurant where I work. We use it to make batters, and blanch vegetables like you mentioned, but also to cook rice. Both jasmine rice and Thai sticky (aka glutinous) rice get rinsed in lime paste water, rinsed more in fresh water, then cooked in fresh water. The explanation I was given is that this makes the water harder, like it is in Thailand, and firms up the outside of the rice grain.

It is important not to use too much lime paste, however, because it causes the rice to turn yellow.

Have you heard of this usage? Can you explain why this happens?

Thanks!!!

Cool Chris,

I had not heard of using it with rice. Did you think it made the rice firmer? I don’t know why the rice would go yellow. Wheat goes yellow in basic conditions due to the modification of flavonoids (apigenin-c-glycosides according to my cursory research) at high pH. Rice bran does contain apigenin, but I don’t know if rice does.

Hi Dave,

I am staging at Noma right now and experimenting with nixtamalizing Danish grains using lye I’ve been making from the combined ash of juniper (probably not the ideal wood, but it’s what I have) and fucus seaweed I foraged here in Copenhagen. The strongest solution I got was about pH 12.8… much better than I was expecting, and I think pretty clear evidence that the combined ash produced NaOH and/or KOH, as hoped. I presented to the other chefs on Saturday night and got a great response. Now, it looks like I will be extending the project (and my blissful time at the Nordic Food Lab) for another week. I’ve relied heavily on your article thus far, and commend you for your incredible work. Now I’m wondering if I can pick your brain on a few issues.

Did you test the pH of your used nejayote? I was surprised to see even my strongest stuff neutral or even slightly acidic at the end. I considered this a positive sign, as some chemical reaction was obviously taking place. But I was reluctant to use loads of my hard-won lye to see how much I would need to go through the whole process and still have alkaline nejayote (which would, to me, suggest that the nixtamalization process was complete). One test I ran suggested that pre-soaking in normal water meant I could get away with using less (or less strong) nejayote, though I consider that far from established. But I wonder why that would be.

Did you always get clear tortilla aromas from your nixtamalized grain? Because, I must say, despite the strong chemical reaction, the difference in flavor and aroma between my nixtamalized rye, barley, oats, and wheat and the boiled controls is so subtle that I hardly know if it exists at all.

I have now heard from both you and my friend Esteban, who is from Chile, that nixtamalizing wheat turns it yellow. This did not happen with my wheat. But I was using nejayote with an initial pH of 12, which is, from what I can tell, very much on the strong side. Is it possible that the yellowing comes from something other than the alkalinity? If so, what?

Is cooking necessary for nixtamalization? With one round of my testing on rye, I was unable to get on the range after putting the rye in nejayote (initial pH of 12), due to a long meeting between Rene and the chefs on staff in the test kitchen. When I came in the next morning, the pH of the nejayote had fallen to 6. I strained the rye and put it in new pH 12 nejayote and cooked it. This, too, was neutral at the end. The rye was good, but not tortilla-like. Anyhow, the dramatic chemical reaction that took place during the overnight soak makes me wonder if cooking is actually essential to the nixtamalization process.

I don’t suppose you would know if there are nutritional benefits to nixtamalizing grains other than maize, though if you have come across any such information, I’d love to know of it.

Many thanks,

David

David, Sorry for the tardiness of this reply,

I had always considered the cooking necessary for the pre-gelatinization of the starches, not so much for the destruction of the seed coat.

I haven’t tested my nejayote, but my understanding is that the commercial ones are still alkaline when they are done (don’t quote me). I’d be curious to see how rapidy the pH changes in your tests. I also think the aroma is formed more when using CaOH, although I don’t remember why I believe that (I’d have to go back and re-read all the papers). Several minutes after you start simmering corn, or rye, the “Cal” smell comes out and you know you will have the tortilla aromas. Those aromas are intensified when the tortilla is cooked.

Interesting about the wheat color. Perhaps your variety is low on xanthophyll and flavones (the stuff that makes it yellow).

Since your comment is from a while ago, please update me on your current tests.

Hi Dave,

Two quick questions about using a basic substance when cooking green veggies.

1. what concentrations?

2. do you think this would work with oil-blanching? I was thinking about doing Chinese green beans but trying to keep them crazy green while still boiling off a good amount of internal water.

Thanks!

Kevin

Howdy Kevin,

I never measured the concentration, but it is small. CaOH is only weakly soluble in water. The easiest way to get a constant dosage would be to make lime water (by saturating CaOH in water and letting the residue settle). Lime water is stable and easy to store, then you can add that to cooking water. Much easier is to add CaOH straigt to the pot. Start with a couple of grams per liter and see how it goes.

With number 2, I think you’d have to soak or pre-water blanch before the oil to get the CaOH to the veggies. Please try it and let me know what happens.

Now that I think of it –the first time you do the tests, swamp the water with CaOH (like 10 grams per liter, which is way too much). This way, you know the effect is working. Then scale way back, and make sure the effect is the same. If it isn’t, dial up the concentration slowly.