by Dave Arnold

This, then, is the second part of the mega cocktail science post. For the science of ice, temperature and dilution, see Part 1.

Here I’ll deal with proper temperature, proper dilution, and the different qualities of shaken and stirred drinks. I will also talk about good batching techniques, and then you’ll get, at no extra charge, the Thomas Waugh section promised last week.

Dilution:

Many folks think all drinks should be diluted some standard amount; 25% is often bandied about. Not true — there is no single ideal dilution. In Part 1 I showed that the average stirred cocktail is both warmer than, and less diluted than, the average shaken cocktail –so at a minimum there are two different ranges of good dilutions: one for shaken and one for stirred drinks. But it’s more complicated still. In a series of blind taste tests with bartenders Kenta Goto, Scott Teague, Eben Klemm, Don Lee, Chad Solomon and Christy Pope, we made Pegu Club cocktails and sidecars with different known dilutions, hoping to find the ideal. No luck. Preferences depended on a number of factors including palate fatigue (is this your first drink, or your third?), and what had been consumed prior and after. A drink tasted balanced at a low ABV (alcohol by volume), went out of balance as the ABV went up, but then come back into balance again at an even higher ABV. The more components there are in a drink –spirits, acid, sugar, bitters, etc. the more complicated dilution becomes, because each component may respond to dilution differently. For more details see Ideal Dilution Through %ABV.

Temperature:

Many people believe drinks should be as cold as possible. Not true. No drink should be served colder than -20°C or it’ll be painful. Straight shots of certain spirits, like 80 proof vodka and aquavit, start to crystallize at about -23°C, so if they are clear they probably won’t hurt. Those same straight shots are really enjoyable between -16 and -18°C, where the temperatures accentuate sweetness, minimize the perception of alcohol, and produce a viscous body that is supremely enjoyable. Lucky for us, this is the temperature range of most home freezers. Vodka in the freezer is a good idea – as you already knew. On the other hand, minus 18°C is waaaay too cold for most booze and for most mixed drinks. Most over-chilled drinks are dull and lack flavor and aroma. Shaken drinks usually taste best between -5°C and -10°C. That’s lucky, because properly shaken drinks are right in that range. Most stirred drinks taste best between -0.5°C and -7°C. Lucky again; most stirred drinks are in that range. These observations are my general rules of thumb derived from side by side taste tests over the years. Many people enjoy over-chilled drinks because they like the sensation of biting cold. That’s fine, of course –but if they analyze the overall drink, they’ll notice that flavor is compromised.

Temperature can also radically affect the balance of a drink. I’ll give you an example:

Bottle Strength GnT’s:

A while back I was in the habit of making bottle strength gin and tonics. I’d re-distill gin to bring it above bottle proof without changing the flavor profile, then add quinine sulfate, sugar, clarified lime juice, a pinch of salt, and enough water to bring me back to bottle proof. I’d chill the whole batch down to -20°C and carbonate it. I kept the bottle in a -20°C chiller and poured shots as needed. By the time the customer drank the shot, it’d be up to about -18°C. Remember when I said most drinks aren’t good this cold? Well, I balanced this drink specifically to taste good at that temp. They were delicious –carbonated, stinging cold, just the right acidity and sugar, not overly alcoholic tasting, with a syrupy body. Problem was, those shots only tasted balanced between -18°C and -15°C. Any warmer and they started to go out of balance –way out of balance. The taste just flew apart. The problem was so bad that I would get visibly angered if people didn’t drink the shot right away. Since I can’t guarantee people will not sit about idling chatting instead of drinking, I no longer serve the drink. Bottle strength GnT’s are an extreme example, but the balance of any drink is affected by temperature.

Postulate of Classic Cocktails

I have distilled many spirits and made many drinks that, like the bottle strength GnT, need precise temperatures and dilutions to be delicious.  I have realized that these spirits and drinks will never become popular, and they don’t have what it takes to become classics. My postulate of classic cocktails:  classic drinks are those that maintain deliciousness over a wide range of temperatures and dilutions – they can withstand bartender abuse and interpretation, and they don’t wither in front of a lazy drinker chatting up their date.

Texture

Temperature and dilution are fairly easy to measure. Texture is much more difficult. After our first Science of Shaking seminar at least year’s Tales of the Cocktail, everyone wanted to know how we would measure texture, and whether a bartender’s shaking style had a significant influence on drink texture. We set out to find the answers.

In our first test we had Alex Day, Kenta Goto, Don Lee, and Chad Solomon all shake daiquiris. Eben Klemm, Audrey Saunders, Nils and I tasted the drinks blind. Apart from varying ice crystal quantities floating on the surface, which we ascribe to straining technique, the drinks tasted fairly similar. See the post here.

That different bartenders using different shakes produced similar drinks, in conjunction with our findings that shaking style and ice types didn’t affect temperature and dilution, led me to believe that unless a drink contained a foaming agent like egg white, the texturizing effects of shaking were fleeting. I figured the air bubbles and ice crystals in a shaken drink just floated to the top and were gone after the first sip. Wrong.

Shaking versus Stirring –the blind-fold taste test:

We gathered another group of bartenders: Eben, Thomas, Joaquin Simo of Death and Co, Dana Cory of Lady Jay’s, Karen Jarman of Painkiller, and Nils, Nastassia, and me. We chose two classic stirred cocktails: the Manhattan and the Negroni. We made each drink four ways: stirred fast, stirred slow, shaken and poured through a single strainer, and shaken and poured through a double strainer. The drinks looked so visibly different that we tasted them wearing blindfolds –a real blind taste test. To my surprise, every one of us was able to distinguish between the shaken and stirred drinks. Almost always we liked the stirred ones and dis-liked the shaken ones. The only exception was the double-strained Negroni, which some people thought was good –but not as good as the stirred. Although these tests didn’t control for dilution, It was clear that dilution wasn’t the only thing making the cocktails different. Our ability to tell the difference between the drinks was maintained for at least 5 minutes, but disappeared by 8 minutes. Contrary to what I had believed, a textural element introduced by shaking was maintained for at least several minutes. Also –turns out we like our stirred drinks stirred, not shaken.

Fake Shake 1:

If shaking really does introduce some lasting texture to the drink, how do you emulate thattaxture in large demos where it is impossible to shake to order? We blind tasted 4 daiquiris: fresh shaken, diluted and chilled in a freezer, diluted and chilled in a freezer then spun in a blender for service, and chilled with Liquid Nitrogen. Everyone liked the fresh shaken best. The Liquid Nitrogen was a close second. The blender was bad –the bubbles were too big and frothy (this is no indictment of blender drinks –this drink had no ice, just liquid). The merely chilled cocktail was what it was –rather flat.

To visualize what was going on up-close, I employed my kids’ toy microscope –the Eyeclops (by the way they make some crazy night vision goggles. I bought them “for my kids”).

We made drinks, poured them on the white table, and took pictures of them with the Eyeclops.

Under 200x magnification, stirred drinks appear blank, but both strained and unstrained shaken drinks had lots of tiny bubbles — straining a shaken drink removes ice crystals, but not air bubbles. Drinks chilled with liquid nitrogen, which aerates as it chills, also had bubbles, but not quite as many as the shaken drink –lending credence my theory that LN is the best chilling mechanism for shaken drinks in super-high-volume scenarios.

Fake Shake 2:

Not everyone has liquid nitrogen, so we tested some easier ways to fake the shake. I made a batch of whiskey sours, some of which I pre-diluted and put in the freezer. At tasting time I shook one drink to order, poured one straight out of the freezer, shook one of the pre-chilled guys in a quart container, and shook the last one in a quart container filled with the springs from hawthorn strainers, for extra aeration. The drinks were noticeably different. One taster liked the drink straight from the freezer –a texture-hater apparently, because he liked the drink shaken with the springs the least. Most people liked the freshly shaken drink best, with the drink shaken in the quart container a close second. The one shaken with springs was similar to the other two shaken drinks, just a little more airy.

Stir Texture = No Texture, and the best stirred drink:

I have been saying for a while that stirring is a technique that chills without providing texture –it adds nothing extra. To test this theory we blind-tasted drinks stirred live versus drinks that were pre-diluted and chilled. They were indistinguishable. The best stirred drinks, therefore, can be made by pre-batching the drink with water and chilling it in a freezer. Just make sure to use a freezer that isn’t too cold. You don’t want to serve the drink much below minus 7C. Drinks made this way are effortless and consistently perfect.

The last question to tackle: how to figure out the amount of water to add to your batch recipes.

Scientific Batch Recipes:

If you want to pre-batch a cocktail and chill it in the freezer, it is helpful to know how much water to add. Diluting to taste isn’t a good idea. It’s likely you won’t be diluting at the proper serving temperature, and temperature has an effect on your perception of dilution. Here’s the best way to come up with a batch recipe:

Gather enough ingredients to make a cocktail and mix them together without ice. Better yet, mix enough for two cocktails and your measurement inaccuracies will be proportionally less; if you make more than two drinks at once the mix might not shake or stir properly. Make sure you measure by volume (most cocktail recipes are by volume, and the density of cocktail ingredients differs widely). Make sure you measure accurately – no “half a lemon†nonsense. Bitters are tough. I tend to ignore them in my calculations unless a lot is included. Weigh the undiluted cocktail as accurately as possible. Now chill the drink exactly as you normally would. If you normally stir for 20 seconds, do that. If you normally shake for 15 seconds, do that. When you are done, strain the cocktail off the ice. It is important to leave as little of the drink in the shaker or mixing glass as possible. Now weigh your drink.  Taste the drink. Do you like it? Then, bang – you know how much dilution that drink should have. If you don’t like it, go back and repeat ‘til you do.

While the above technique is a good start, it introduces major inaccuracies because some of the cocktail remains trapped in the ice after you strain it — we call this trapped liquid ‘holdback’, and you need to correct for it. Here’s how: after you strain your cocktail, dump the ice into a tray, recover the last bit of liquid from the ice, weigh it, determine what percentage drink you think it is (this is a non-scientific, best guess kind of thing –like hey that tastes like 75 percent water). Do the math (see below) and re-calculate the cocktail based on the estimated holdback.

Two Example Batch Calculations (With and Without Holdback Correction):

Whiskey Sour Basic Recipe

2 parts whiskey 45% abv

1 part strained lemon juice

0.5 parts 1:1simple syrup

Tiny pinch salt

Total Batch: 3.5 parts

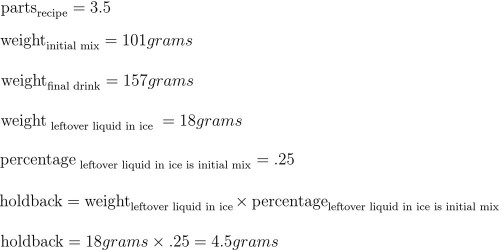

We jiggered up one cocktail and it weighed 101 grams. Eben Klemm shook it using his normal technique. When we strained the drink it weighed 157 grams (it was -4°C). We then dumped the ice into a tray and recovered 18 grams of liquid. We tasted it and it seemed to be about 25% initial mix. This is unscientific, but the best we could do without good equipment.

Givens:

Â

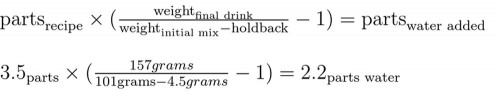

Water calculation with holdback (more accurate):

Â

Water calculation with holdback:

Â

Â

Manhattan Basic Recipe with proper dilution:

2 parts rye whiskey 45%abv

1 part sweet vermouth

some bitters (sorry, I said bitters were tough)

1.5 parts water

Total batch: 4.5 parts. Total dilution (percent of initial mix volume in water added to drink): 50% ! Approximate Final ABV: 20%

Secret Bonus for Reading this Far –Salt:

The secret ingredient in our cocktails isn’t love, it’s salt. A pinch of salt added to most cocktails brightens them up and rounds out the flavor tremendously. You don’t need a lot. Add so little you don’t even perceive saltiness –I call it “sub-threshold salting”. Sugar and vanilla also do interesting things in sub-threshold quantities. When I distill liquor, I usually add a small amount of salt and sugar – not enough sugar to add sweetness.

Bonus –Thomas Waugh from Death and Co tells us how all this business has affected the way he tends bar.

Â

Â

by Thomas Waugh

Upon completing our investigation on the variables of stirring, here are some humble suggestions for the everyday bartender:

1.  Chill your mixing (stirring) glass — ice works, as does a fridge or freezer.

2.  If making multiple drinks, build the shaken drinks first, but without ice, and set aside.

3.  Continue to build the stirred drinks in the cold mixing glass.

4.  Stir without breaks until the stirred drink is cold (we found that 45 seconds is an ideal stirring period).

5. Crack some ice to maximize surface area. Note: too much cracked ice will hinder the control of your dilution rate.

6. Pour stirred drinks first.

5.  Finish the order by adding ice to your shaken drinks and shaking, as shaking is a much more efficient technique.

Hey Dave,

Any chance you could get a better read on the “holdback” by weighing the used ice, spinning it in a salad spinner (or something similar), then reweighing? Not sure it would be much more accurate than the SWAG approach (scientific wild assed guess), but seems possible that it’d get you closer to reliable and repeatable results.

Cheers

Hey Chris,

I’m gonna use SWAG. I already love swag at conventions (even if it means outfitting my small kids with liquor brand baseball caps) cause I can’t resist free crap. Now I can use SWAG when I’m working too!

The main inaccuracy comes from not being able to establish the water to mix ratio in the liquid left on the ice. It might be possible to spin the cocktail right away (instead of straining). That would work, assuming that the liquid near the surface of the ice isn’t water enriched from the get-go. I’m not sure.

Hi Dave,

Interesting comment on the sub taste level salt and sugar addition, I could not agree more. Sub taste level salt helps in coffee a lot as well (I always add a pinch to the ground coffee).

Also I don´t now any sauces that don´t benefit from minute amounts of sugar (and a tiny bit of acid). Sauces usually contain plenty of umami taste from the demi glace already, but this finally leads to my question:

Have you ever experimented with adding some MSG to drinks in a sub taste level?

(With umami you probably can add a lot cause most people will never realize the taste anyways, but I was thinking about small quantities, especially with Cocktails based on butter or cream….)

I haven’t tried MSG in drinks. Interesting idea.

MSG would be especially good in, say, a Bloody Mary, to pump up the natural umaminess of the tomatoes.

Another thing: in sweet and acidic drinks, I’m pretty sure that dilution affects perception of sweetness and acidity differently, and thus balance between the two, though I’m not sure if this is a purely perceptual effect or has something to do with buffering by organic acids (eg citric)

also, I think this post deserves a prize for best ever application of LaTeX.

Thank you for noticing the LaTeX! I think you are right about the dilution affecting sweet and acid differently.

Any chance we can get the negroni batch recipe? And any favorite gins to use for it? Thanks, they’re my favorite cocktail and I would like to introduce more people to them.

You can fudge (or SWAG, I suppose) a relatively good batch recipe for a Negroni working backwards from the Manhattan. Each consists of 3 parts spirit/vermouth to start with. Assuming a London Dry Gin at 40%, Campari at 25% and Sweet Italian Vermouth at 15% you can probably guesstimate added water required at about 55% initial volume – that’s with me assuming that lower total abv results in greater dilution. To be honest, test it out with three – one with 40%, one at 50% and one at 60% (Navy would call that “bracket the target”) and then tweak on a single drink to decide your batch dilution.

Dave and team – was pointed to your blog after a session with The Training Team in Edinburgh today (Bacardi-Brown Forman’s UK bartender roadshow) and gotta say this makes for fascinating reading. Great work, I really appreciate what you’re doing and thank you for sharing it with the rest of us.

So for the nonprofessional, retired old fart who has been making and drinking martinis, manhattans, negronis, and side cars for 50 some-odd years, using ice from the ice maker, cracking or not cracking it, can you recommend the method that would provide the most satisfying cocktail? Shake? Stir? How long? Crack the ice? Don’t crack the ice?

Thanks.

Salt! Haven’t tried it in cocktails. But it’s my fault for not thinking of it yet — fo quite some time I’ve been tossing a tiny pinch on top of my ground coffee before it gets french pressed. Does wonders to kick out bitterness and inflate the roastiness.

I liked the idea of “sub-threshold salting†for cocktails! I’ve blogged about salt in coffee and salt with fruit earlier – it sounds strange, but it really works!

Again – thank you for a good post!

Thanks for reading!

I’m confused. Either this is a thinko or your articles contradict each other slightly. In this one you say “In Part 1 I showed that the average stirred cocktail is both warmer than, and more diluted than, the average shaken cocktail.” In part one, however, you say “Because stirring doesn’t reach equilibrium, stirred drinks are warmer and less diluted than shaken cocktails.”

Which one of those is correct? And if the statement in this article is in fact the correct one, doesn’t that mean you’ve left unexplored the exact nature of the tipping point between light stirring that won’t ever cause a drink to reach equilibrium and more vigorous stirring that will?

Should say warmer than, and less diluted than. I’ll check it!

I just started cooking and what not this year and I f*$%ing love carbonation too. It makes everything better! What would you recommend for a home chef guy thinger? I am in awe.

I should probably do a carbonation post soon. There is a list of parts in one of the forums threads.

Stir for 45 seconds? Are you mad? Maybe in a perfect bar where you have all the time in the world but in a venue on Friday or Saturdy night where people may be 2 or 3 deep at the bar and your servers are all screaming for drinks for the dining room where on earth do you have almost a minute to stir each and every cocktail? Please let me know where this Shangri-la of bars exist because I’d love to work there. I make a Manhattan, I roll it and give it a few stirs in the glass and it’s done. The patron can stir the hell out of it if they wish, however I still have chits coming out the wazoo and much more important things than to stir a cocktail for 45 seconds to achieve equilibrium. Whilst all this academia is nice let’s not ignore the practical side of working in a busy bar.

Hello Cutter,

That’s the point! Stirred cocktails don’t reach equilibrium in the real world –and you don’t want them to –they’d be too diluted. The fact that stirring doesn’t reach equiilibrium makes stirring more complex than shaking.

Dave,

Crappy place to post this request, but I am looking for quinine in a liquid form, such as you used in your ‘perfect Gin and Tonic’ video. Thanks.

Howdy Ian,

I use Quinine Sulfate powder which I purchased from Spectrum Chemical online. Convince them you are a lab or school or something. Be careful with the stuff and make tinctures of it to use in drinks. Never use it directly.

Hey Dave,

Do mind if I use some of your data for a training manual I am writing for a Resturant group. I would love to get your permission to use some of the data. Perhaps the microscopic pictures of stirred vs. Shaken. Good stuff these bartenders need to read this material.

Josh@hawthornbev.com

Of course we would accredit you rightfully

Sure. Contact Nastassia if you need more info.

whats the best email contact for both of you ? thanks again. I would love to send you more information on who this is for etc..

lopez.nastassia@gmail.com