posted by Dave Arnold

This is the fourth Cocktail Science shaking post. The previous are:

1: Thermodynamics of chilling: why drinks get so cold

2: Temperature, Dilution, and Ice.

3: Why do my shaker cans get stuck together?

We had established in Cocktail Science 2 that the type of ice (within reason) and the shaking style (within reason) didn’t appreciably affect the dilution or temperature of a cocktail. All reasonable shaking styles produced drinks within a couple of percent ABV (alcohol by volume) of each other. If temperature and dilution aren’t the main factors distinguishing shaking styles, what are? Most people think the answer is “texture.â€

Consequently, we’ve been asking people a simple question: How the hell do you measure a drink’s texture? Many people propose checking drink aeration by measuring density. I don’t think aeration is the most important aspect of most drinks. Some wanted to check the ice crystals produced by different shaking techniques. Again, are ice crystals the only determining aspect of a drink’s mouth feel? What if we measure density and ice crystals? In the end, all these approaches are flawed because they don’t really address the REAL problem: What does the drink taste like?

We were discussing this with Audrey Saunders from Pegu Club and decided that instead of trying to measure texture, we should get four badass bartenders together, have them shake a standard drink, and see if we could tell the difference. Audrey graciously offered to host the event at Pegu Club last Monday.

The bartenders were:

Alex Day, of Death and Co., and the Franklin Mortgage and Investment Co. (and the Tales of the Cocktail shaking seminar!); Kenta Goto, of Pegu Club; Don Lee, PDT, Momofuku Ssam; Chad Solomon, Milk and Honey, Pegu, Flatiron Lounge, Little Branch, etc., etc.

All serious players.

The tasting panel was:

Audrey Saunders, grande dame of the cocktail world, owner of the Pegu Club, and friend of The FCI; Eben Klemm, head of beverage for the B. R. Guest Restaurant Empire, and head of the Tales of The Cocktail Shaking Seminar; Nils; Myself.

Â

The drink, as chosen by Audrey: the daiquiri. She intimated that any other initial choice would be preposterous. I wasn’t about to argue.

We decided that the drink would be pre-mixed, so there could be no difference in the mix from bartender to bartender. The recipe was: 2 parts white rum, 3/4 parts 1:1 simple syrup, 3/4 parts lime juice.

The pre-mixed drinks were also pre-portioned for each bartender. Each bartender was given identical shakers with 12 total Kold-Draft ice cubes. We didn’t limit how or how long the bartenders shook. That was the point of the test, to see if those factors made a difference. The tasting panel was not allowed to watch the bartenders shake and was not allowed to see the bartenders pour or place their drinks. All drinks were poured into un-chilled fizz glasses. We chose fizz glasses because they allow for easy checking of drink volume. They were un-chilled because we didn’t want to augment shaking styles with additional chilling.

Here is the first shake:

We didn’t taste this one right away. We wanted to see what happened to the drink texture if we waited. Obviously, Drink 1 had more ice crystals on top and Drink 2 had the fewest. Drinks 3 and 4 look similar. You can’t really judge final drink volume from this shot because of the entrained air. We let the drinks sit for 20 minutes and here is what happened:

The drinks have leveled out a lot after they have settled. There are some ice crystals left on top but not many. Drink 1 still has a slightly higher volume, because most of those extra ice crystals have melted into water. We called this effect “secondary dilution.†When the ice crystals are present, they don’t represent dilution, because they haven’t melted yet.

When these drinks were tasted 20 minutes out they were remarkably similar. Even Drink 1 wasn’t that diluted. Audrey expressed a like for Drink 3. Drink 2 tasted slightly more lime-y, sharper, than the rest—presumably because it had a lower dilution and the acid is more pronounced at lower dilutions.

OK, now to taste a fresh shake:

We tasted this one immediately. Notice the second shake looks a lot like the first, except there are more ice crystals in Drink 2. This was the beginning of a trend we saw. The drinks started becoming more similar. This is because we made the crucial error of allowing the bartenders to hear our discussion. That isn’t a mistake we’ll make again. These drinks tasted remarkably similar. Drink 1 had the crunchiest texture. Audrey again liked Drink 3. Eben, Nils, and I liked them all. Drinks 2 and 4 had the most lime flavor, but the difference was marginal. After we had been tasting a while, we noticed that the surface effects, ice crystals, air, were gone after the first couple of sips and the underlying drinks were almost the same.

Here is our first postulate:

Most of the texture and taste differences between shaking styles (in drinks without viscosifying agents like egg) are confined to the top of the glass.

This makes sense because ice and air float. We wanted to test this theory, so we decided to taste the next drink quickly from the bottom of the glass with a straw before we sipped normally. We were out of the original batch, so Audrey had a batch made with cane syrup just to mix things up:

Notice Drink 4 is short this time, as is Drink 3. They all tasted similar from the straw, except Drink 4 which was sharper, because the lime was accentuated by the relative lack of dilution. It didn’t taste as concentrated as it looked, however, so I wonder if dome drink accidentally got left in the shaker or spilled. When tasted from the top, the texture difference were much the same as they were for the second shake. The cane syrup made a sweeter drink than the simple, because we didn’t correct for different Brix levels, but it was still balanced. Eben liked Drink 2 best. Nils and I like it boozy so we liked Drink 4, although I also liked the texture of Drink 1. Audrey went Drink 3 again.

Then we did a shake with agave nectar instead of simple:

These drinks are almost identical (excluding surface texture). None of us liked them, however, and we vowed to never again make a daiquiri with agave syrup.

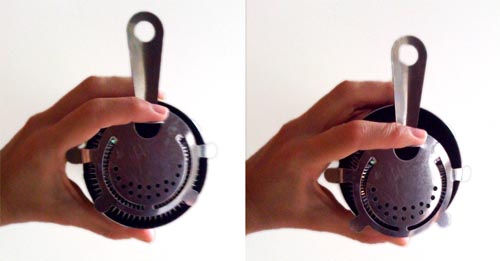

After the official tasting, a discussion of “open gate, closed gate, or half gate?†erupted. I didn’t know what they were talking about so I figured I was about to be let in on a mystical secret. Here it is: Bartenders adjust the amount of ice crystals they let into the drink by controlling how far they push down on the hawthorn strainer as they are pouring.

Closing the gate holds back more ice, producing a shorter pour with fewer crystals, and opening the gate does the opposite.

Just for fun, I shook a standard daiquiri using the crazy-monkey technique. The crazy monkey involves shaking so hard and so long that your body feels like it is flying apart. The idea is to see if a ridiculous and unfeasible shake appreciably alters the drink. Here is the drink:

Audrey and Nils thought the drink was more diluted. Eben thought it was a little more diluted, but not so diluted that it was outside the range of normalcy. It did have a lot more ice and air than the other drinks. What is interesting about this is that although the drink was a little more diluted, it wasn’t diluted as much as you’d guess from how crazy I went with it. To me, this was consistent with our results from the shaking seminar.

The monkey shake leads us to the subject of our next cocktail post: our perception of dilution. The crazy monkey did taste more diluted than the normal drinks. If the other drinks were 21-20% ABV, the monkey tasted like 18-17. We couldn’t measure the alcohol, but the truth is, the monkey was probably only 1 or 2% ABV below the other drinks, not 3. From tests we have run earlier, we suspect that there are certain drops in ABV that register more than others. The difference in taste between a 21 and a 20% ABV drink isn’t as much as the difference between a 20 and a 19% ABV drink.

So who was whom?

Don revealed to us that he was doing a modified version of the hard-shake, and intentionally producing copious crystals. Alex had to jet to work before the discussion at the end. Chad and Kenta had no comment. Pegu had opened for business and customers were rolling in, so we hightailed it out.

Till next time.

Had I known you had a “crazy monkey shake” up your sleeves, I would have insisted on video for the Savory Cities interview!

some further helpful post on shaking theory. and a confirmation, so far, that shaking method does not tend to make the difference. probably the different straining methods are far more distinguishable.

Was everyone happy with the amount of ice in the shaker? In my opinion and experience, different bertender preferences, shakers and shaking styles also tend to be developed to go along with different volumes (not to mention sizes) of ice.

Howdy, Yes they were.

Excellent, again, gentlemen. Did you measure dilution percentages? Eyeballing they look like they are around the canonical 25%….

Another great experiment. Please keep them coming! This is pioneering work!

Very interesting article. I’m glad you are taking this as seriously as you have taken your food posts. I was surprised to see that a technique many of us implement wasn’t used here. Why aren’t you using a conical strainers in addition to the classic Hawthorne strainer? It would completely extract the “open gate, closed gate, half gate” variable within this discussion.

Ah Nils, a tough job you have there…! I’ll have to ask Tom about that conical strainer tonight at Craigie..

Hi,

I’m a bartender at the Oberon Grill out in Eureka CA, after having made my way here from NYC. I am grateful to have found your postings on the science of certain heretofore overly simplified/underdiscussed areas of mixology. While there is much artistry involved in the craft, there also much science within the artistry and I am thankful for your rewarding inquiries so far in this regard.

Hopefully, while happily lapping up intel, I can here and there offer something of value back to the discussion.

And so here goes a coupla things- vis. shaking vigor, length of shake and aperture of gate discussion:

1) I have percieved (and maybe just in my own deluded and self-serving mind) a benefit from longer and fairly vigorous shakes of cocktails which have the addition of what i’ll call ‘bountifully concieved’ liqueurs, i.e.- Benedictine, Chartreuse and the like… I have long suspected that there are cogeners and/or other elements within them that become active positive factors in the finished cocktail either directly through taste/aroma or texture (or both) only after suffering the extra friction and micro-oxidation that may achieved through longer and more monkey-like shakes.

…Crazy?

2) Often cocktails, esp. the ones intimated above, involve the inclusion of fresh lemon or lime juices. I presume that, aside from their varying influences on aroma and flavor, these ingredients serve the primary function of providing acidity to the cocktail. Acidity, as I understand it, is a fairly volatile quality when present in liquid- tending to want to escape local confinement as soon as possible through aromatization. Wouldn’t, then, vigorous shaking have a tendency to reduce the overall acidity of a cocktail, esp. in the case of ones involving fresh lemon/lime juices?….. implying, then, a fairly direct way for the bartender to manage the role of acid/acidity in their cocktails… Maybe perhaps?…. Or maybe perhaps silly?

Thanks again to all involved in the creation and continued growth of this resource.

i root

eureka ca

I’m not sure I understand your/ the article’s stance on the textural aspects of the cocktail. ice crystals and aeration, while not the most important aspect of a drink add a textural component as enjoyable and satisfying when well achieved as any counterpart in food. Many a chef would cringe to read words diminishing the value of texture and mouth feel in food. If it is so inconsequential, why all the whipping, meringues, mousses, purees, foams etc.? surely the answer isn’t artistry alone; mere presentation.

A drink with equal dilution and temperature but none of these qualities would be to me as a delicious but tough steak.